The Lost World

The Secret Life of Wold Newton

By John Dale

My grandmother Alice Lambert was nearly ninety when she climbed onto her sideboard to brush down a cobweb. As she reached up, she lost her balance and fell. She was found in her home, Groom’s Cottage, Wold Newton, Lincolnshire, and taken to hospital. She had broken a hip.

While lying in bed, she drifted into a delirium and said to me: ‘The boys, the boys…all those boys, they’re all dead.’

I didn’t know what she meant and asked my mother.

Twenty-seven years earlier – on 5 December, 1943 – my gran, then Alice Dale, had been working as housekeeper to Mrs Louisa Burkinshaw at Scallows Hall, Wold Newton. It was a Sunday and during the week, as diary entries show, there had been trouble with poachers. Earlier that day Mrs Burkinshaw, a widow and member of the local landed gentry, had attended mass at the nearby All Hallows church. Now she was having a nightcap of cocoa, perhaps prepared by my gran. It was 8.30pm and bedtime was approaching. Sleep was no longer easy in what had once seemed such a remote, peaceful valley. Now the nights were filled with the roar of scores, sometimes hundreds, of bomber planes heading for Germany, flying from neighbouring RAF airbases and, if spared, limping home again.

Alice Lambert, John Dale, Susan Dale with one of the Ollard children, at Scallows Hall, Wold Newton, circa 1951.

Two miles away a Lancaster III, of 101 Squadron, was taking off from RAF Ludford/Kelstern, and climbing into a dark sky. The pilot was 21 years old, assisted by six other aircrew, aged 19 to 30.

The plane was on a training flight which might have explained why it failed to gain the necessary height as it entered a bank of cloud.

It had been in the air for less than a minute and could be heard if not seen by Wold Newton villagers below when it emerged from the cloud. It was too low.

There was neither height nor time to pull up or for the crew to bale out. It was travelling at about 200mph when it clipped the tops of branches. Then it destroyed a line of trees and ploughed into the ground. As it slithered along, its wings and tail ripped off and it burst into flames, spraying burning oil in a series of explosions. The flames flashed along the hedges and into the beeches nearby.

The bomber had avoided Scallows Hall – by thirty yards.

In the scale of things, that was a very narrow escape for the house and the two women within its walls. The Lancaster was 70ft long with a wingspan of 100ft and weighed 25 tons. The great mass of metal and wood dug a long furrow, broke up and turned into an inferno. Inside the hall the women must have thought night had turned into day and their world was coming to a firey, ear-splitting end.

On the other side of the village, Mrs Burkinshaw’s brother William Wright, the Squire of Wold Newton, had attended Evensong at All Hallows. On returning home to The Manor, he had lit the dining room fire and eaten supper. Then he saw his gardener Bill Day come rushing in looking alarmed and exclaiming: ‘Scallows Hall is on fire.’

The Squire left and hurried up there along with the the Wold Newton Fire Brigade and their trailer and pump, which was seeing its only wartime action. They were accompanied by village lads on their bicycles. They could see the glow of the flames against the night sky.

As he noted, the fire had spread and there was a huge trail of wreckage, with one landing wheel hurled into a neighbouring field. The members of the aircrew were pulled out. They were all dead. The rescuers laid the seven burnt bodies along the drive of Scallows Hall – the pilot Flying Officer Francis Oliver, 21; Albert Wells, 20; William Reid, 30; John Anderson, 30; Raymond Spierling, 19; Stanley Burton, 20; and Robert Bradbury, 20.

‘Plane down,’ wrote Squire Wright in his diary. ‘East of house strewn with wreckage. House intact. Ambulances and cars…all very quick/quiet. Reports going off from burning plane. Oil and burning stretching into the Park with broken trees. Seven poor bodies taken away.

‘All very agitating but must be thankful that neither Louie nor Mrs Alice D(ale) or house were harmed.’

Next morning Squire Wright returned to inspect the devastation in daylight.

‘Pleasant morning, not cold…Go round the awful scene of destruction. Evidently plane came down in the Park about 20 yards south of the gate into side road…ploughed up ground deeply…its pathway littered with thousands of parts – engines, iron plates, splinters, bits of wings and tails, simply a heap of scrap iron. Apparently no damage to house or stables or outbuildings.

‘All hedge from Park gate to close gate burnt away, most of hedge of garden screed the same, 3 or 4 beech burnt…one of the undercarriage wheels flung into the middle of the East field intact…Chief officer comes over, very silent. Horrible scene of destruction.’

The Squire sent a letter to the War Damage Committee and the wreckage was put under guard. That itself was not without problems.

He noted: ‘Call at Scallows, nothing moved, 4 sentries go on and give interminable trouble to Alice D…Louie has trouble (with) her soldiers, policeman comes and gave them a shock.’

On the Sunday, the regular service was held at All Hallows church, as the Squire dutifully recorded.

‘Hardly anybody attend. Seven poor young men from Ludford Aerodrome remembered at Mass. Louie and Alice can’t come, of course. Hear later that debris being removed…Hear also that another plane from Ludford down.’

At Scallows, cranes loaded the last of the wreckage onto lorries. As the plane was cleared away, the mood of the village began to lift. The following weekend it was Alice Dale’s 63rd birthday and then Christmas cards were exchanged. Christmas Eve arrived, bright and frosty in the morning, and as a night mist shrouded the village, a large congregation attended Midnight Mass. With low visibility, the blackout curtains at the church windows were hardly necessary.

Afterwards Wold Newton returned to its normal rhythms, although ones still disturbed most nights by the roar of Rolls-Royce engines in the blackness overhead.

A stone cross was erected by the Squire in Scallows Hall Woods, as a memorial but also in gratitude to the crew for missing Scallows Hall. It stands there today alongside an old beech tree, its bark apparently scorched, perhaps from those flames.

In the years that followed, my gran never mentioned the crash to me. Only in her hospital delirium did it re-emerge: ‘The boys, the boys…all those boys, they’re all dead.’

Alice Carline meets Erasmus Dale

My grandmother, Charlotte Alice Carline – known as Alice – was born on 18 December 1880 in the North Lincolnshire village of Ulceby. She was the daughter of William Carline (1852-1930) and his wife Rose Florence (nee Smith 1861-1921). William was a groom, probably to Lord Yarborough on the nearby estate of Brocklesby Park, and the family lived at ‘North West Side of Road Leading from Brigg to Church’.

Alice told me in about 1963 that she went into service when she was seven. It seemed an unhappy memory for her. In the 1891 Census, the Carline family had moved from Ulceby to Audleby Villa, Caistor. The details are: William Carline, 43, groom/domestic servant, born Thornton; Rose F, 29, wife, born Barnetby; Arthur E, 16; Charlotte A(lice), 10, scholar; John C, 8; Rose F, 7; William E, 5; Harriet H, 3; Lucy A, 10/12 (months?).

Ten years later the 1901 Census shows Alice, aged 20, working as a domestic housemaid for her brother Arthur Carline, 26, at his baker’s shop and home in Junction Square, Barton-on-Humber. There is a visitor listed – a 21-year-old man called Erasmus Dale. Other occupants of the address are Arthur’s wife Mary, 26, and Alice’s brothers John, 18, and William E., 15, both described as bakers/journeymen. In effect they are all living over the shop, useful in the case of a bakery where the hours are long and hard.

Perhaps Erasmus and Alice were already ‘courting’ which might explain his presence. Perhaps romance had yet to flourish. Anyway in 1903 they are married in the Glanford Brigg district.

Who was Erasmus Dale? In the 1911 Census, he stated he was born in Ebberston, a small village near Pickering, in the North Riding of Yorkshire, the son of George Dale (b 1853 and his wife Sarah (nee Lumley 1858-1935). By that year he and Alice had moved across the Humber and were living at 6 Bethnal Green, Newland, Hull, between Blaydes Street and Beverley Road. He described himself as a ‘tobacco manufacturer’.

But after eight years their marriage had produced no children, and would continue to fail on that front. After a further seven years, the Dales were still childless. This must have been distressing for both especially as by then Alice was reaching her late thirties and must have given up hope of motherhood.Then fate dramatically intervened. It would have seemed like a miracle, a gift of life during the carnage of the First World War.

Alice was almost 39 years old when she was offered a baby of her own, and not just as a loan. It was 1918 and the little boy was born on 19 September of that year, just seven weeks before the end of the war. However, his birth was not officially registered, and there would be no birth certificate or record of adoption – an informality not uncommon at the time, a period of huge social disruption caused by war losses. The sole documentation was a note apparently written by the mother authorising Alice to take charge of the child, to care for it as her own, which she duly did. It would be forty years later before she allowed her son to see that note indicating that she was not his real mother, as he had hitherto believed. It came as a deep shock to him, although one he would not talk about.

Alice and Erasmus named the baby Kenneth Erasmus Dale. Perhaps it is significant that they included ‘Erasmus’ in the middle. Did this mean Erasmus Dale was the real father but by another woman? Could that other woman be one of Alice’s sisters? In a crisis, had Alice offered to take care of the child – at the same time solving the ache of her own childlessness?

(Alice’s youngest brother William Edward Carline enlisted in the First World War. “Corporal 191 5th Liverpool Regiment, then 2nd Lieutenant 1st/5th Lincolnshire Regiment. Wounded. Lived at Waverley House, Westfield Road. His mother ran a carriage business in Junction Square.” http://bartononhumberatwar.blogspot.co.uk/2012/08/barton-soldiers-enlisted-in-great-war.html).

Alice and Ken Arrive at Wold Newton

Kenneth Erasmus Dale, born 19 September, 1918. A studio shot. Formal adoption did not exist in England until 1927. Most adoptions were informal, with no central register. They often took place within families. Alice may really have been Ken’s auntie, with his real mother being one of her sisters. It was wartime, a period of social upheaval and uncertainty, and his father could have been a soldier, even one who was killed or seriously maimed. This is speculation. Ken was in his forties when – needing a passport – he discovered he had no birth certificate because his birth had never been registered, and Alice had concealed that she was not his birth mother. This was normal practice then because of the stigma but it still came as a shock to him. He never discussed it with anyone except Eileen.

A year later Alice moved to Rothwell as the Rector’s housekeeper and twenty years later transferred to Scallows Hall, working for Mrs Burkinshaw.

Meanwhile young Ken, having left school at 14, had joined that great mass of peripatetic workers who, from the mid-1930s, were being deployed on large-scale government civil engineering and rearmament projects, in preparation for a resumption of hostilities against Germany. First he went to the North-East, then to Gloucestershire, helping to build airfields. These became active as war commenced in 1939.

In late 1941 Alice caught the bus from Wold Newton to Grimsby, visited the Westminster Bank and withdrew £10 from her savings account. She then travelled to Bourton-on-the-Water, Gloucestershire. She had hardly been out of North Lincolnshire. Visits to Grimsby and Hull were exciting events and this was probably the longest journey of her life. Two hundred miles from home, she attended the wedding of her son to Eileen Minchin and, that afternoon, started back north as a passenger in a relative’s car.

The wedding. Alice Dale is seated second from left, next to her sister Nellie, Nellie’s husband Bob, and another sister Lucy. Best man is Ken Buckingham, then Ken, Eileen (in a pink crepe dress, bolero jacket and hat, with two orchids), her father Bill Minchin. At front her sisters Thelma and Peggy, and her mother May, with a third sister Nancy just behind.

The newlyweds, Ken and Eileen, boarded a train and arrived at Grimsby Town station in the evening just in time to catch a bus. It took them seven miles into the countryside to Binbrook. It was wartime, late, cold and bleak. Ken tried to hire a taxi but failed. So, in snow and ice and in pitch blackness, he and his new wife picked up their suitcases and trekked the two miles of narrow, undulating road until they saw the lights of Scallows Hall.

It was past midnight by the time they walked up the drive and knocked on the door. Alice was there to welcome them, with Mrs Burkinshaw. They put down their bags, worn out by the wedding and a long journey. This was their honeymoon and they stayed over Christmas. Then Ken returned to the Army and Eileen to her parents in Gloucestershire.

Two years later, the Lancaster crashed outside Scallows, embedding itself in the collective memory of Wold Newton.

Alice weds Harry

Late that year, 1943, Alice’s husband Erasmus died In Hull aged 64. As a ‘tobacco manufacturer’ he was probably a smoker – like most men then – and it would not have been conducive to good health. At the same time the Squire’s groom Harry Lambert lost his wife Elizabeth, aged 69. By the following year Alice and Harry had decided between them how best to solve the loneliness of their mutual widowhoods.

‘Lambert is to be married again on Thursday Next at 8am, the usual Execution hour!!’ writes the Squire’s younger brother, Parsons Wright, in his diary of 18 September 1944.

Next day Squire notes in his diary: ‘Get presents for Alice and L (Lambert), cross and chair for Alice, silver knives for L. Parsons will join me in the latter.’

On the Wednesday, Parsons writes: ‘Lambert to be married at 8am tomorrow. “Loud Cheers”!! This business leaves me cold somehow. I’m not yet quite right in my inside but pretty good at times.’

Squire’s diary: ‘Get flowers for L’s wedding and do up Church vases. Parsons and I give Lambert a set of silver knives, Louie and I a gold cross and chair for Alice.’

The day of the wedding, Thursday 21 September, starts with an autumnal mist. With the ceremony arranged for 8am, people have to get up at the crack of dawn.

Harry Lambert, Alice Lambert. Possibly at their 8am wedding. Note Lambert’s watch chain. Both he and Bill Minchin were proud of their pocket watches.

Squire (in almost illegible handwriting): ‘Foggy warm morning and up pretty early. Wedding of Harry Lambert and Charlotte Alice Dale, I give the bride away. Louie, Mrs Bejoyne and Alice come down in hired car. Mass follows the wedding. Then we all go and drink the bridal couple’s health and have a very good wedding cake. They go off in hired car about 9.30am. Even Polly goes to wedding and reception, Parsons only exception. Louie goes off about 10 with Parsons.’

Parsons (in copperplate handwriting): ‘Foggy first off, keeps fine but still. Lambert’s wedding at 8am. I get there and stop for Mass afterwards. They leave for Huddersfield!! Run Loo back in the morning.’

The register showed Harry to be aged 67, the son of Harry Lambert, a farm foreman.

With Alice away, Louie Burkinshaw was without her as housekeeper at Scallows Hall. What was to happen now that she had married Lambert who lived at the other end of the village, in Groom’s Cottage?

On the Sunday, Parsons writes: ‘I wonder how Loo has got on today. A very difficult situation, something will have to be done about it.’

Squire may have been equally worried about their sister’s isolation: ‘I would have gone up in the afternoon, had to keep to the house.’

After six days, the honeymoon in Huddersfield over.

Parsons: ‘Lambert and his wife return…!’

Squire: ‘Lambert and Alice return in the evening.’

Afterwards, the tug-of-war over Alice is resolved. She leaves Mrs Burkinshaw’s service at Scallows and became the Wrights’ housekeeper at The Manor, moving into the Groom’s Cottage with Harry.

Meanwhile, the news is being sent by letter to her son Ken serving in the Eighth Army in North Africa and Italy. The war comes to a victorious end and he received an early demobilisation in 1945 on condition that he settled in the Grimsby area, which needed skilled labour to recover from the 1930s Depression and German bombings. He had become a joiner and wheelwright by trade and so his practical skills were greatly valued.

To begin with, he and Eileen – then with their three-year-old daughter Susan – lived with his mother and Harry Lambert at Groom’s Cottage. Then Ken found a house in Cleethorpes and in 1946 I was born there, suddenly, in the kitchen.

Over the following years, my sister Susan and I used to board the Binbrook bus – just as our parents had done on their honeymoon – to visit my grandmother, usually on a Saturday afternoon. It dropped us at the Ravendale junction and we would walk to Wold Newton. In the early days, we’d be with our mother and father. On other occasions Lambert – even my gran called him by his surname – would be waiting for us in his black groom’s breeches and carry me and Susan in turn on his shoulders. He spoke differently from people in Grimsby and taught us to say‘wa’er’ for ‘water’, adopt his Lincolnshire country accent and pour hot tea into the saucer and blow on it just to be bad mannered. His austere look in the photo above belies a mischievous, teasing manner.

From the early 1950s, Susan and I travelled there on our own. That Ravendale walk seemed a long one, especially the return journey as darkness fell and the trees seemed to come alive against the sky. Gran took a pride in us and we’d accompany her to The Manor to see the Wrights – the Squire (she called him ‘Master’), Mr Parsons and another sister Miss Margaret.

They were kind to us and in summer we would sit at the table in the garden room and have honey for tea, collected from their own hives.

Outside, Parsons, who was stone deaf, would lean down and bellow at me: ‘DO YOU WANT A RIDE IN THE CAR, JOHN?’

This was exactly what I wanted and I’d nod and he’d push open the stable door and get out the car. In my flawed memory, it was a 1928 Bullnose Morris but records show it was more likely a green Austin 12, with canvas roof, which had once been used to pull the fire brigade pump. My sister and I – and my father if he was with us – would climb aboard. One could hardly see through the yellowed glass, the steering wheel wobbled alarmingly and the suspension was like a sponge. Mr Parsons, whose eyesight was only marginally better than his hearing, would be laughing and shouting as, like a version of Mr Toad, we’d charge down the Manor drive, out of the gate and hurtle straight up the hill opposite. Fortunately there was little other traffic except cows, sheep and horses. It was the wildlife that I felt sorry for. I loved these rides mainly because they were so alarming. We’d roll over the hills, hanging on for dear life.

The Wrights’ sad year

At Groom’s Cottage, Lambert kept a beautiful vegetable garden and a pig called John, which was named after me and spent his days grunting in a sty at the back while digging his snout into buckets of swill. When I was five, a van arrived and Lambert persuaded John to get into the rear. Fortunately they had the right John and he was driven away. Later that day, the van returned with huge pink haunches of salted bacon which were hung in the ‘cold house’. I was unsure where they came from. They lasted for months.

There were other local people whom we met – Roper (?), who occupied a house next to the gate to the church and usually carried a scythe over his shoulder ready to curb the grass, and my gran’s two immediate neighbours. On one side was Mrs Reeves’s ‘shop’ where we could choose from a tiny selection of penny and halfpenny sweets and bottles of White’s dandelion and burdock ‘pop’. On the other was Bill Hall – ‘Shep’ – who, to me, looked big and powerful like Garth from the Daily Mirror comic strip. But it was an illusion. He shared his house with his mother, who was bent double, and even then we recognised their poverty and social isolation. As a shepherd working the fields, it didn’t matter how he dressed but he was an example of endemic rural deprivation. According to my gran, he had once gone into Grimsby in his shepherd’s clothes – which were old, threadbare and all he possessed – and had found himself being laughed at by the townies. He never went back. He just stayed in and around the village, his flocks, his mother and their home which was ramshackle and scarey, like something from Grimm’s fairy tales.

He had a horse and two-wheel cart and I’d ride on it and go to the wheatfields during the harvesting. His sheep dogs would run alongside. They were working animals, not pets. At night, if they barked without cause, we would hear him beat them into submission. They’d yelp and then fall silent.

Diaries make clear how close Harry Lambert was to the Wright family. He was a frequent companion to the Squire and others on trips round churches, and often referred to only as ‘L’. One day he’d be cutting the Squire’s hair, the next out in the fields helping to bring in the harvest.

In February 1950 the postman arrived at The Manor to say he couldn’t get an answer at Scallows Hall. Lambert was sent up to investigate and found Mrs Burkinshaw – Louie – dead in her bed. This year was to prove a turning-point for the Wrights. The following October, they also buried their sister, Polly (Mary).

One month later, Harry himself died and was buried on Remembrance Day, 11 November.

The Wright family, outside The Manor, 1893. Squire Wright stands on left, then a student at St John’s College, Oxford. He’s next to his sister Miss Margaret. Louisa Burkinshaw is sitting at the front, on left, next to her mother Eliza, notably difficult. Sitting on the right is young Parsons, still at school.

Afterwards, my gran remained at the groom’s cottage alone.

There was no running water in the village. We used a pail to collect water from the pump across the road and stored it in a stone urn in the pantry. I’d study the small creatures swimming in it. They were destroyed when it was boiled for tea or – my own preference – disguised by the adding of Robinson’s Barley Water. We didn’t worry. In the same way, when using the toilet (in the outhouse, emptied monthly) you had the company of scores of fat spiders to study at your seated leisure. (On 27 August 2015 John Dale visited Newton and was invited into Groom’s Cottage by its present occupant, Julie. He took the following film… https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m-54arJ8vgY. It can be found on Brentford TV)

I reached my teens and started cycling the seven miles to Newton by myself, or with schoolfriends. It was a journey through time as well as place. It was such a unique contrast with industrial Grimsby. In the summer sunshine, the village was a lost world, preserved in its own valley and period, and I was an explorer. Others found it equally fascinating, both for its geography and history. At The Manor I’d point out the array of neatly-arranged shoes under the staircase, multi-shaded patent leather which my gran dusted regularly. They had not been worn for decades, and hinted of the Wright’s past social life so different from growing isolation of their present.

At 80, Alice carried on

I was drawn to the house and to its ageing unmarried occupants, relics in their purity and restraint of a Victoria-Edwardian age, almost the last of their kind and of their bloodline. The Squire wore a pale linen jacket. Miss Margaret wore a tweed jacket and peered alarmingly from beneath the brim of a trilby. Mr Parsons, the more extrovert and jolly, would be in a waistcoat. In a way, I saw my gran as the fourth member of this eccentric set, ever present and an essential part of the mechanism. She was an intelligent, hardworking woman. They relied upon her as much as she relied upon them.

Like its occupants, the house too was a leftover from a bygone era, shunning modernity, comfortable and reassuring. At its best it was filled with the scent of flowers, fruit and vegetables picked from the gardens, and of game freshly killed in the fields. From the kitchen would come the smell of cooking as Alice, sleeves rolled up, prepared a meat pie for lunch. At its worst, it seemed austere and lonely, with life passing it by, a waiting room for the world beyond, the anteroom to a family mausoleum.

At lunchtime on hot days, if finances stretched to it, I’d cycle to the Clickem Inn and buy a bottle of Hewitts pale ale to quench my thirst for adulthood.

My gran, who was under 5ft in her later years, was slightly younger than the Squire and Miss Margaret but a contemporary of Mr Parsons. In 1960 she turned eighty yet continued in her role, hardy and resolute from a lifetime of working in service. I honestly believe the concept of retirement hadn’t penetrated the minds of this unusual quartet. Certainly, Alice would never have considered it. She had her duties. It was her job, her purpose, to clean the house and prepare the meals. She also used to take care of Mrs Ollard’s children. My sister liked helping her.

Bill Minchin, Alice Lambert, May Minchin in front garden, 12 Rissington Road, Bourton, early 1960s. Bill wearing tie, May in best frock. Why is Alice visiting from Lincolnshire? Looks like a special occasion. Any suggestions?

We took a photograph showing gran, me and my sister with one of the Ollard babies, at Scallows.

I would stay several days at a time at my gran’s, sleeping on a horsehair mattress laid on the planks of a springless wooden bed. I was free to cycle and explore the neighbouring hills and valleys and to visit The Manor. I loved the library upstairs with its collection of Victorian novels – G. A. Henty’s Wulf the Saxon and Charles Kingsley’s Hereward the Wake – many dedicated to the young Squire, Margaret and Parsons on their birthdays, in the 1890s, when one sensed the Wrights were a more active part of the Lincolnshire squirearchy.

At my gran’s we had once eaten rabbit pie but now those animals had been afflicted by myxomatosis. Villagers would turn up at the door with a pheasant or a wild hare hanging from their fist. She’d stand at the sink, roll up her sleeves, skin it and put it in a pot. She’d cook it on her black kitchen range, with a coal fire in the middle heating an oven on one side and a kettle and pans on the other. We, and most of the village I think, loved jugged hare, served cold and jellied, with homemade bread.

Things did change. The outside world began to intrude and my gran bought a small television, black and white. To start with, she became addicted to Dr Finlay’s Casebook which held a mirror up to her own rural existence even if it was based in 1930s Scotland. Then one evening Dr Finlay brought modernity too close. He dealt with an unwanted pregnancy. She never watched or mentioned it again.

She also told me: ‘I support the Conservatives because my father always voted for Mr Gladstone.’

I said: ‘Mr Gladstone was a Liberal, Gran.’

This stunned her into silence. Despite that, she continued to vote for Sir Cyril Osborne, the Tory MP for Louth.

An era passes

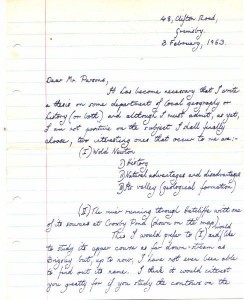

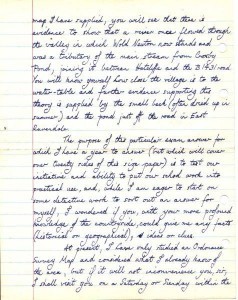

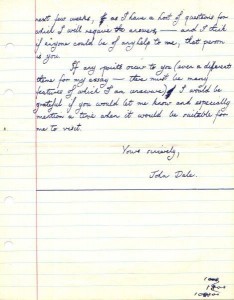

In 1963, I sent a letter to Mr Parsons explaining I was writing a thesis for my geography ‘A’ level exams about the geology of Wold Newton, Ravendale and Croxby Pond. While he and Squire had sounded like characters from Evelyn Waugh in their writings, I was more prototype Adrian Mole, aged sixteen and three quarters: ‘…if it will not inconvenience you, sir, I shall visit you on a Saturday or Sunday within the next few weeks, as I have a host of questions for which I will require the answers – and I think if anyone could be of any help to me, that person is you.’

He later put my letter between the pages of his diary where they remained undisturbed for 50 years until found by John Ollard.

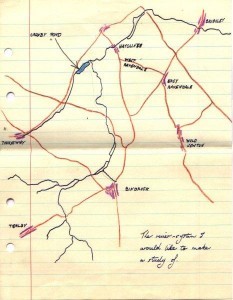

I did visit and Mr Parsons dug out a large map for me. I sat down with him and my gran – I am not sure if Miss Margaret was bedridden by then – and we spread it on the table in the room overlooking the garden. It showed not just their land holdings but the topography in detail – especially the glacial overflow at Ravendale – and it became the basis for my project and enabled me, in a schoolboy way, to produce a decent piece of work.

That year Alice put on her best hat and fox stole and attended the marriage of my sister to John Waite, in Grimsby.

That year Alice put on her best hat and fox stole and attended the marriage of my sister to John Waite, in Grimsby.

There are many other recollections from Wold Newton.

When the Squire died, his will allowed my gran to continue to live at the cottage for as long as she wished. Time slipped by and I moved away but we would all visit her. Eventually Miss Margaret and Mr Parsons passed on and gran broke her hip while reaching for cobwebs and needed a stay in hospital, which was when she became delirious. Incapacitated and her services no longer required, she left her home and Wold Newton and settled down in Crow Tree Nursing Home, Louth. After a lifetime spent looking after others, the time had come for others to look after her. She deserved no less. She died in 1974, aged 93. On 17 September she made her return to the village to be buried at All Hallows, thirty years and three days after her wedding there. In torrential rain under thunderous skies, the mourners and pall-bearers slipped in the mud as they struggled up the hill to the church. It rained even more when the coffin was lowered into the grave, an atmospheric funeral which seemed to suit the mood. She was laid to rest not far from the Wrights with whom she spent so much of her life.

Alice Lambert left few written records of her life except her bank book. I looked at it and it showed that after the First World War she had travelled to the Westminster Bank, Grimsby, once a year in order to deposit exactly £20 each time. She saved £20 a year from 1920 to 1939. Then, in 1941, there was the first withdrawal – £10 to attend her son Ken’s wedding. After that, she resumed saving.

Although her housekeeping pay was probably meagre – that was standard then – she was able to save from it because of the way the village economy worked, with homegrown vegetables and livestock and game, and a network of informal support. With a roof over her head guaranteed, she believed herself to be fortunate and was always able to put money aside. She bought me a bicycle and, later, a 98cc James motorbike, modes of transport intended to encourage my visits to break the monotony as she, and the Wrights, grew older. I still feel guilty that I didn’t visit enough. She took my sister and I for a week’s holiday in Bridlington. To her, the state pension seemed extravagant. The idea of dying in debt was both improbable and unthinkable.

Like her, my father Ken enjoyed a long and healthy life, dying aged 88 in 2007.

Ordinary lives from a lost world

Overall, it is reassuring to see that Wold Newton has not changed too much. When occasionally I pass The Manor and my gran’s cottage, I still sense a magnetic pull. I find myself being drawn back fifty years, into the presence of Alice, the Squire and Miss Margaret. I smell the flowers from the garden and a meat pie cooking in the kitchen, and I hear Mr Parsons booming from far off: ‘DO YOU WANT A RIDE IN THE CAR, JOHN?’ The answer today would be the same as yesterday: an enthusiastic yes. And next moment I see us flying down the Manor drive, out of the gate and straight up the hill opposite, scuffing the grass verge and sending the pheasants exploding into the air.

John Dale

20 May 2013

(With much additional material from John Ollard. Also sincere thanks to woldnewton.net)