A Much-Wanted Child: Kenneth Erasmus Dale.

The War Baby: An Answer to Alice Dale’s Prayers

by John Dale

I went to Hull to walk in my father’s footsteps. It was a Saturday morning in March and I tried to cast my mind back nine decades. We usually think of the past in black and white, like old silent movies, but this time the sunlight brought out the reds of the Victorian and Edwardian brickwork. The sky was blue and cloudless, the faces crisp with cold. As I passed the shops and houses along the Beverley Road, it felt like a journey of small discoveries. Dad seldom discussed his childhood, and certainly not these earliest years. He was very much a wanted baby but it was not easy to acknowledge. The world was very different then.

The year 1918 was one of terrible social upheaval, with many of Hull’s young men dying in the trenches of the Western Front, or returning maimed and shell-shocked. The city had been bombed 12 times by Zeppelins, killing 54 people and destroying the Holy Trinity Church. Casualty lists were posted up daily for everyone to read. Thousands wandered through the streets dressed in mourning black. Behaviour changed. Family structures fell apart and re-formed, so that life could go on.

In a time of uncertainty, there were several things this new baby must have symbolised when it was delivered on 19 September, seven weeks before the end of the war. Hope. The future. A genetic promise for the next generation, and generations yet to come.

Ken’s mother was probably one of his aunts. Whatever the provenance, the child must have seemed like the answer to the prayers of such a devout churchgoer as Alice Dale. By then Alice and Erasmus Dale, both 38, had been married for fifteen years. They were childless. To them, this would have been a blessing, almost a miracle, a tiny presence which could fill a dark emptiness.

But Alice was not alone in seeking this opportunity. The baby was also wanted by Alice’s brother Jack (John), then aged 36, and his wife Alice, 34. They too were childless. The couples argued over who should take possession.

Kenneth Dale, aged about seven, with Alice. She always called him ‘Kenneth’. Studio shot, circa 1925, when they were facing financial ruin.

Alice and Erasmus took precedence and the baby was handed to them. Like most such arrangements at the time, there was nothing formal and all the knowing adults conspired to hide the truth. No one visited the Register of Births, Marriages and Deaths to fill in a form giving details, as was the legal requirement. In that way the baby was a secret. The sole documentation was a note apparently written by the mother permitting Alice to take custody, to care for him as her own, which she duly did. It would be forty years later when Ken, in applying for a passport, discovered he had no birth certificate. When pressed, Alice allowed him to see the note indicating that she was not his real mother. Although by then he may have had his suspicions, it was still a shock. He told Eileen but no one else, and then without detail. It was Eileen who told myself and my sister.

The baby was named Kenneth Erasmus – Erasmus suggesting that perhaps Erasmus Dale was the father even if Alice was not the mother. But we can’t be sure. It may simply have been a further step in the concealment, to deceive neighbours and schoolteachers and to shield the little boy from the prevailing prejudice.

The Marriage of Alice and Erasmus

Charlotte Alice Carline – known as Alice – was born on 18 December 1880 in the North Lincolnshire village of Ulceby. She was the daughter of William Carline (1852-1930) and his wife Rose Florence Carline, nee Smith (1861-1921). William was a groom, probably to Lord Yarborough at nearby Brocklesby Park, and the family lived at ‘North West Side of Road Leading from Brigg to Church’.

Alice told me she went into service when she was seven. It seemed an unhappy memory for her. In the 1891 Census, the family had moved from Ulceby to Audleby Villa, Caistor. The details are: William Carline, 43, groom/domestic servant, born Thornton; Rose F, 29, wife, born Barnetby; Arthur E, 16; Charlotte A(lice), 10, scholar; John C, 8; Rose F, 7; William E, 5; Harriet H, 3; Lucy A, 10/12 (months?).

The next record is the 1901 Census. It shows Alice, aged 20, working as a domestic housemaid for her brother Arthur Carline, 26, at his baker’s shop and home in Junction Square, Barton-on-Humber, on the south bank of the Humber estuary. There is a visitor listed – a 21-year-old man called Erasmus Dale. Other occupants of the address are Arthur’s wife Mary, 26, and Alice’s brothers John, 18, and William E., 15, both described as bakers/journeymen. In effect they are all living over the shop.

Perhaps Erasmus and Alice were already ‘courting’ which might explain his presence. Perhaps romance had yet to flourish. Anyway in 1903 they married in the Glanford Brigg district.

Who was Erasmus Dale? In the 1911 Census, he stated he was born in Ebberston, a small village near Pickering, in the North Riding of Yorkshire, the son of George Dale (b 1853 and his wife Sarah (nee Lumley 1858-1935). By 1911 he and Alice had moved across the Humber and were living at newish terraced home, 6 Bethnal Green, Newland, Hull. He described himself as a ‘tobacco manufacturer’ and they had a newsagents and tobacconist’s at 116 Beverley Road. For some reason it was in Alice’s name – C. A. Carline. Perhaps that was because the money for it had been put up by one of her business-minded brothers, such as Arthur.

Three years later, on 4 August 1914, Britain declared war on Germany and a great social upheaval began.

6 Bethnal Green, Hull, 2014. New door and windows, in an area now popular with students and ethnic groups. Back in 1911, this would have been a new house in a lower-middle class neighbourhood favoured by clerks, shopkeepers and other white-collar workers. Although modest in size, it looks well built.

116 Beverley Road in 2014. The newsagents shop was probably built out on the forecourt. It’s been knocked down to make a parking spot.

Beverley Road Swimming Baths. Perhaps young Kenneth swam here. People would also use it for the ‘slipper baths’ – so they could bathe in plenty of hot water unavailable at home.

By 1918, after 15 years of marriage, the Dales were still childless and Alice was reaching her late thirties. She must have given up hope of motherhood when fate dramatically intervened with the birth of Kenneth. It was Alice who was given his care.

Who was Ken’s real mother? Again we can only speculate. At Ken’s wedding in 1941, two of his aunts made the long journey to Bourton on the Water. They are pictured at the wedding.

The wedding of Ken and Eileen, Bourton, 1941. Alice Dale seated second from left. Lucy is standing behind her.

One was Lucy Ann Carline, who would have been 28 in 1918. The 1911 census shows her as unmarried and working as a domestic servant for her brother Jack, a grocer, at 68 Wincobank Avenue, Shiregreen, Sheffield. It was Jack who also wanted to adopt the baby.

In 1918, Alice, a devout Christian, would probably have turned to her parish priest, the Rev. G. J. Jordan for support and advice. In her later years, Alice would often refer to ‘Canon Jordan’. In 1917 he came as curate to Holy Trinity, Hull, at about the time it was badly damaged by Zeppelin bombing, and was in charge during the period his superior, Canon Buchanan, was serving with the armed forces in France. Then he was eight years at St Thomas’s, Hull, leaving in 1928 to become Vicar of Bridlington. He seems to have been an inspirational figure and a departing tribute declared: ‘Had had to face criticism as a public servant but he had survived the test. All his tremendous enthusiasm and energy had been put into his work, which had been in one of the poorest districts of the city.’ In response Jordan said that in Hull he ‘has spent the eleven happiest years of his life… The parish priest has to deal with people and he is generally a happy man.’

Financial Disaster

Meanwhile Alice and Erasmus continued to run their shop. For both, it would have been evidence of achievement, rising from the labouring/servant classes to having their own business. On the 15 May, 1924, the Hull Daily Mail published the following news item:

‘“I AM DYING” Man collapses in Beverley-road shop. A man staggered into the shop of Mr C. A. Carline, newsagent, of Beverley-road this morning and collapsed, crying out: ‘I am dying. I have been dying all night.” Mr Carline, interviewed by the Mail, said that about 11.30 the man came in and dropped across the counter, where he began moaning. He would not give any name or address and nothing could be done with him.

‘A large crowd quickly gathered outside the shop, and Mr Carline sent for the police. P.C. Robinson arrived and conveyed the man in the police ambulance to the Royal Infirmary, where he was attended by Dr Robson, who found him to be suffering from heart trouble and detained him.’

Mr Carline? The C. A. Carline in the shop’s title referred to Charlotte Alice Carline. Why was the business using her maiden name? Because it was backed by one of her brothers, both shopkeepers? And why was Erasmus Dale called Mr Carline? Perhaps the journalist made a mistake. Or it may have had other significance.

On 31 January 1925, the Hull Daily Mail printed another item: ‘LOCAL DEED OF ARRANGEMENT Dale, Erasmus, trading as C. A. Carline, 116, Beverley-road, Hull, tobacconist and newsagent.– Liabilities unsecured, £620; estimated net assets, £419. (At 2014 prices, those sums would be £33,000 and £22,000 respectively).’

This was followed by another notice on 18 June 1925: ‘Public Notices. Deeds of Arrangement Act, 1914. In the Matter of a DEED OF ASSIGNMENT for the benefit of Creditors, executed on the 21st day of January, 1925, by ERASMUS DALE (trading as C. A. Carline), of 116, Beverley -road, Hull, Newsagent and Tobacconist. NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN that all persons having any CLAIMS against the ESTATE of the above named…and who have not already sent in the Claims are requested to send particulars thereof to G. A. Ridgway, of Cogan House, Bowlallay-lane, Hull, Incorporated Accountant, the Trustee under the above mentioned Deed and to execute an assent thereto on or before the 15th day of July next, after which date the Trustee will distribute the Assets of the Estate ….’

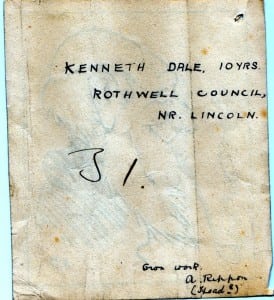

Put bluntly, the business had gone bust. With almost no state welfare to fall back on, Alice and Erasmus faced financial ruin, and now they had six-year-old Kenneth to care for. It was perhaps then that the Rev Jordan came to the rescue. At some stage Alice got a job as housekeeper to the curate of Rothwell back in North Lincolnshire – at the Old Rectory, in School Lane, Rothwell. She and Ken took the ferry from Hull across the Humber and went to live in what is now a grade II listed building next to a medieval church, St Mary’s.

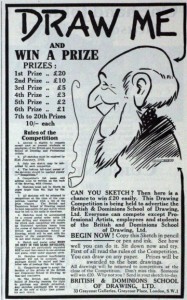

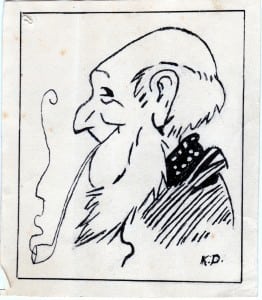

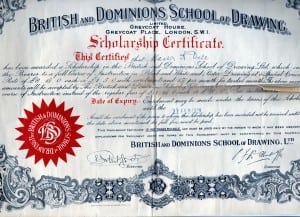

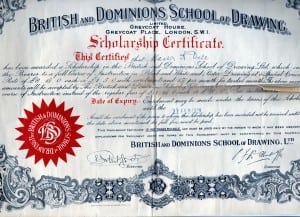

It was then he must have seen the following newspaper advertisement. It was from a company, the British and Dominions School of Drawing Ltd, of Greycoat House, Greycoat Place, London SW1, which ran correspondence courses, popular in those days. “Can you sketch. Then here is a chance to win £20 easily.”

“This certifies that Master K. Dale has been awarded a Scholarship in the British and Dominions School of Drawing Ltd., which entitles the Bearer to a full course of Instruction in Black and White and Poster Drawing at a Special Concession Rate of £8.15.0 (£8.75p) cash or £1.5.0 (£1.25p) with enrolment and 15/- (75p) per month for twelve months….instead of the regular fees of £15.15.0 cash or £18.0.0 in instalments. Enrolment may may be made….until 22 Feb 1929.”

According the Eileen, Ken did not take up the offer because Alice could not afford it. Living in as a housekeeper, her pay would have been meagre, perhaps £50 a year. The sums mentioned would have been way beyond her means.

Apart from this incident, we know little about Ken’s formative years at Rothwell. He did not discuss them.

By 1932 he had left school and was working, first in a blacksmith’s shop – he learned how to be a wheelwright – and then as part of the government’s mass mobilisation of men employed on large civil engineering projects and, later, rearmament as another war with Germany loomed. It was rearmament – building Little Rissington airfield – which took him to Bourton in 1937. (See Eileen and Ken: The War Years on this website https://www.minchinsofbourton.co.uk/2013/07/25/love-war-2/

The Lincoln Castle in 1977 – one of the Humber ferries which sailed between New Holland and Hull. Alice and Ken would have known these well, as did most North Lincolnshire people, and they created an air of excitement and romance as they set off on the two mile crossing. John Dale used them weekly when on the Lincolnshire Times in 1964 and, to his simple mind, Hull would loom up like an exotic foreign port. Link below for a You Tube movie. The paddle steamers were eventually displaced by the Humber Bridge. One sister ship, the Tattershall Castle, became a bar and party boat moored permanently on the Thames Embankment near Waterloo Bridge where John Dale frequently gazes at it with fond nostalgia.

Link below for a Humber ferries movie…

Alice continued at the Old Rectory in Rothwell until 1940 when she switched employer and moved deeper into the Lincolnshire Wolds, to Scallows Hall, Wold Newton, to work for Miss Burkenshaw. Upon the latter’s death, she became housekeeper to Squire Wright at the Manor at the other end of the village. (SEE ‘LOST WORLD’ on this website https://www.minchinsofbourton.co.uk/2013/07/13/alice-lambert-dae/

Erasmus Dale remained in Hull, dying in 1943 – which freed Alice to remarry, to Harry Lambert. I remember a large wood and leather trunk stamped ‘Erasmus Dale’ in her bedroom. Ken bore that rather unfashionable middle name. For many years Erasmus Dale seemed a strange, mysterious figure. At least we have solved some of the mystery.

Although Alice’s shop failed, her two brothers prospered as shopkeepers. Bill moved from Barton to the bigger, more bustling Hull.

In the Hull Daily Mail of 26 March 1942, the following job advertisement appeared: WANTED, 2 Girls, 14-16, for Bakehouse.–Apply W E Carline & Son, 9a, Havelock-st.HDMail.

On 7 June 1944, another one said: Shop assistant Wtd., young girl or woman exempt from N(ational) S(service); good wages paid – W. E. & Son, bakers and confectioners, 745, Hessle-rd.

William Edward Carline had enlisted in the First World War. “Corporal 191 5th Liverpool Regiment, then 2nd Lieutenant 1st/5th Lincolnshire Regiment. Wounded. Lived at Waverley House, Westfield Road. His mother ran a carriage business in Junction Square.” http://bartononhumberatwar.blogspot.co.uk/2012/08/barton-soldiers-enlisted-in-great-war.html).

Another advert showed that in 1950 a grocery shop was being run by J C Carline Ltd, 429, Hessle-rd, Hull. This is Uncle Jack – who had wanted to take on Ken back in 1918. He died in June 1978 at his home in Scarborough, where he had retired. Although quite well off, he did not leave anything to Ken because – according to his solicitor via Eileen – ‘he was not part of the family’. Make of this what you will.

Eileen suspects that Ken may have realised in childhood that his origins were uncertain. She told me: ‘Ken never really referred to her (Alice) as his mother. He used to call her ‘the old lady’. I have wondered if he suspected she wasn’t his mother all along.’

Alice’s shop went bust in Hull, mirroring what had happened to Edward Wood’s pawn shop in Cheltenham, triggering his suicide in 1902. Mr Wood’s granddaughter Eileen married Ken. Neither seem to have discussed this coincidence, or even to have been properly aware of it.

Inconvenient truths were hidden. People rose up and slipped down the social scale with alarming ease. It was too painful to spend time looking back. They saw only the sunny uplands of an affluent future, one which would arrive in the 1950s. Life was not just harder but different, especially for Ken who bore the stigma of his birth. Today it is difficult to grasp how cruel people were to those born out of wedlock. It had to be hidden at all cost. Hence, he was a man without much past, preferring a present and a future.