May Wood and Bill Minchin: Drama of the Early Years

How May Minchin Recovered from Childhood Tragedy.

This is the oldest photograph the site has at present (August 2013) of May Minchin. It shows May Wood – who later married Bill Minchin – sitting on the knee of a woman, probably her Auntie Ada, and looking like a porcelain doll. May is one or two years old so it dates from 1893-94.

Alongside her is her mother, Alice Ann Wood, aged 22, future grandmother to May’s daughters Eileen, Peggy, Nancy and Thelma (had Alice lived). In the front, posed on cushions, are May’s older brother Will and step-sister Nancy. Another sibling, Ted, has not yet been born. Perhaps Alice is expecting him in this picture.

CLICK TO ENLARGE: mesmerising. May Wood, aged two sits on the knee of her Auntie Ada Goode (probably); her mother Alice Wood, nee Goode, is in the white blouse; in front are May’s brother Will and step-sister Nancy. The clothes and setting are those of a well-off middle-class family. This contrasts with the Minchins – living 20 miles away in Bourton – who were proud but humble agricultural labourers, definitely not middle-class.

Alice Wood was born Alice Goode on 28 April 1871 in Walton on the Hill, Liverpool. Her father was Thomas Goode, Master of Walton Workhouse. Her mother, also named Alice Ann Goode, was Workhouse Matron.

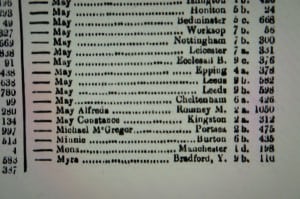

After losing one child, Thomas left the Workhouse and became landlord of the King’s Arms, Ormskirk. When widowed, he remarried and moved to the Sherborne Arms, Cheltenham. (FOR DETAILS, SEE ‘LIKE A DICKENS NOVEL: THE GOODE LIFE 1809-1901’, on this site)

33 Sherbourne Street, Cheltenham 2018. The Sherbourne Arms was saved from demolition in 2012 and converted into homes.

Alice moved with her father to Cheltenham and there, in October 1889, she married a man named Edward Wood. He had been married before and had a young daughter, Nancy. Alice was 18 and Edward was 35, an apparently prosperous businessman, with a pawnbroking and jewellery shop on a prime site, 199 High Street, Cheltenham (occupied by Boots the Chemist a century later). Edward was the son of William Wood (1807-1878), born 1807 West Dean, Gloucestershire, died 1878 Cheltenham, and Mary (Edwards) Wood, born Abergavenney, Monmouthshire 1814, died 1893 Cheltenham; he was grandson of Edward (b 1771) and Ann (b 1776) Wood, both of Gloucestershire.

199 High Street in 2013. This was the site of Edward Wood’s pawnbroking shop. The family, including May, were living here by the turn of the century.

Edward Wood had been working as a pawnbroker’s assistant to the shop owner Mr Solomons from as early as 1874. He is traceable because he was a regular witness at the Police Court in relation to people trying to pawn stolen property. As such, he dealt daily with the town’s poor as they sometimes crossed the line into minor criminality. His first case, when he was 20, was on 20 October 1874 and involved a widow who had stolen a butcher’s saw worth 1 shilling (5p). In another case a woman who had pawned stolen clothes told the police officer: ‘I am not sorry you got me. My husband’s ill-treatment caused me to do this. I cannot live with him and I would as soon be in prison as out.’

In time Edward Wood took over the business. An advertisement in the Gloucester Citizen 24 August 1887 reads: ‘E. Wood, successor to J. Solomon, 199, High Street, Cheltenham. The oldest established Pawnbroking Business in the county. Cash advanced to any amount on plate, watches, jewellery, &c; secrecy strictly observed.’

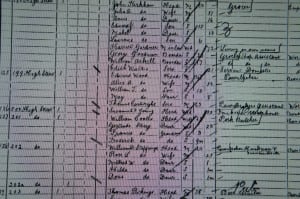

The 1891 census shows them living at a fashionable address, 18 Christchurch Villas, Cheltenham. Also listed is a daughter Elizabeth, 16; a son William, two months; Alice’s sister Ada Florence Goode, 16 (May’s Auntie Ada); and a visitor Annie A. Kirkham, also 16.They had a 14-year-old girl, Elizabeth Taylor, living with them as a domestic servant.

Christchurch Villas. No 18 would have been at the end but has been demolished. Smart but nothing as prestigious as the next address, Oriel Villas.

Oriel Villas is now gated and secured under CCTV cameras. No 3 is at the far end. It was a five minute walk from the pawnbrokers’ shop in the High Street. Did Edward Wood overreach himself? Was this the cause of the terrible tragedy?

The following year, at the time of May’s birth – 1 May 1892 – the family have moved to 3 Oriel Villas. The other woman in the picture may be Alice’s sister, Ada Goode, who would then be about 19. Having come from Liverpool, she seems to be staying with the family and doing work such as confectioner’s assistant, that is, working in a sweet shop. Then in the 1901 census their address is 199 High Street, living over Edward’s pawn shop. There is Edward, Alice and the two children, William and May. They also have the benefit of a servant, Thomas Cartwright, described as a pawnbroker’s assistant. There is no record of the younger son, Ted, then six, living with them, or of her step-daughter Nancy. Edward’s older daughter, Elizabeth, 26, had presumably left home.

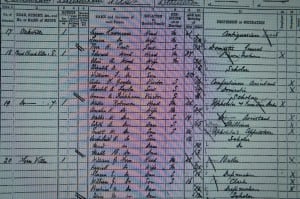

1901 Census. May is aged 8 and the Woods are living at 199 High Street, probably over the pawnbrokers

The 1893/94 photograph is a well-posed picture probably taken by a professional. It is set in a back garden against a brick wall covered in greenery. The grass is unkempt but otherwise the group have been carefully styled in order to project middle-class Victorian values and that most prized of social assets, respectability. It shows a young mother’s pride in her children. Hair and clothes are immaculate, shoes polished and shiny. Will displays a head of tended curls and wears a sailor suit. Alice clutches a book in her lap with a hand displaying at least one ring on her wedding finger. Two other books have been placed on conspicuous display and the items of furniture hint at a taste for chinoiserie. The women have fresh flowers pinned to the fronts of their blouses. They don’t smile but that was normal for the time. The sitters have been told to hold the pose for several seconds because of the camera’s slow shutter speed. They have been asked to stare straight at the lens and not blink. On the right Nancy, who is kneeling awkwardly on a cushion, has broken the injunction, moved and blinked and so is slightly blurred. In contrast May complies and sits perfectly still, determined to hold her expression but at the cost of looking rather serious for one so tiny. Yet her prettiness still shines through, as it did for the next 100 years in real life, and will forever through this photograph.

Despite its creases – or perhaps because of them – the picture exerts a power which reaches across the generations. Gaze at these faces long enough and the unblinking stares of the sitters come to life, drawing you into this eternal moment, insisting they are but a veil away, challenging you to believe otherwise, mesmerising and all-seeing.

Edward Wood is not in the picture. By 1900 his pawnbroking business was incurring problems and he faced ‘pecuniary difficulties’. Despite this he attended a ‘smoker’ – a smoking party – at the Working Men’s Club in the High Street near his shop (where the family were by now living). It was to give a send-off to a trooper being dispatched to South Africa to take part in the Boer War. The Cheltenham Chronicle said: ‘Mr Edward Wood made some congratulatory remarks in his characteristic way, and a most enjoyable evening was spent.’

May Wood. On the reverse, it says: ‘For Miss Hyde. From Mr and Mrs Wood. Taken when three years and a half old.’ The studio is Greenway Bros. at 339 High St, Cheltenham, just down the road from Edward Wood’s shop at no 199. Around Christmas 1894, which explains why May is buried beneath layers of clothes and fur, as well as wearing good leather boots. Here she looks a beautifully dressed middle-class child, before disaster overtook the family. The photo would have been taken in monochrome, then skilfully coloured by hand. Again May is unsmiling but that was normal in photos at the time.

A window May probably looked out of daily as a child. The view from 199 High Street where the family moved after leaving the luxury of Oriel Villas.

Edward Wood suffered bouts of severe depression for which he underwent treatment but it was unsuccessful. He jumped into a pond and died in Cheltenham on 4 February 1902. Apart from the grief, the impact on his family was severe at a time of limited welfare.

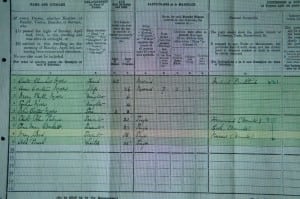

The National Probate Calendar 1902 states: ‘WOOD Edward of 199 High-street Cheltenham died 4 February 1902 Administration (Limited) Gloucester 20 June to Mary Ann Wood spinster Effects £1117 14s. 8d.’

His wife should have inherited as his next of kin. Why did she not do so? What was the legal impediment? Why did his estate go to his sister, Mary Ann Wood, age 58? In 1891 Mary had been living over the shop at 199 High Street with their widowed Welsh-born mother, also named Mary, then 77 – sharing it with four pawnbroker’s assistants. Despite being a businessman, Edward died without a will. If so, he must have known the repercussions would be disastrous. (This is being researched) It was easy in those days even for a middle-class family to lose its mark of ‘respectability’ and slip down the social scale. Life descended into a desperate struggle. Alice found it hard to cope with the remaining two children in her care, William, then eleven, and nine-year-old May (Ted, six, and step-daughter Nancy were already absent).

A difficult period followed.

However, May seems to have made a recovery from this setback, probably through displaying the intelligence, charm and talents which were to serve her well for the rest of her life. The 1911 Census shows that May, then aged 18, has moved from Cheltenham to Bourton-on-the-Water. She is working as a domestic nurse at the home of Dr Walter Moore, medical practitioner, caring for his three children Mary, 6, Evelyn, 4, and John, 3. She is the junior of the servants, alongside a housemaid and a cook. Perhaps it was here that May first learned to recite the wonderful verses with which she would one day entertain her own children and grandchildren.

The address is given as ‘The Cottage’ but the Moores lived at The Mill House, Lansdowne Road. It is now a grade II listed building and an archeology site.

1911 Census shows May working as a nurse (domestic) at Dr Moore’s house in Bourton looking after three young children. The census also shows her brother William Thomas Wood, 20, to be living in Worcester, and working as a drapery salesman.

May meets Bill Minchin

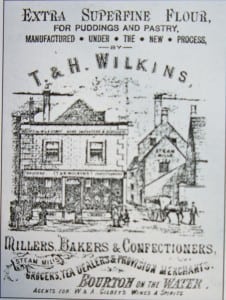

In time May began courting a local lad, Bill Minchin, who worked for the village baker, T. & H. Wilkins, in the High Street. She may have met him when she went to buy the daily bread. Bill’s was an extremely tasking job, requiring him to help bake the bread very early in the morning and then spend the rest of the day doing his rounds delivering it to the people of Bourton and the surrounding villages. He used a horse and cart, doing a 14 hour day, an 80 hour week. Because of the physical demands, and the importance of supplying bread, it was a ‘reserved occupation’. He was not called up into the military during the 1914-18 War and so escaped the slaughter in the trenches of the Western Front.

He was probably still living with his parents, John and Ann Minchin, in their overcrowded cottage in Sherborne Terrace, just beyond the Duke of Wellington.

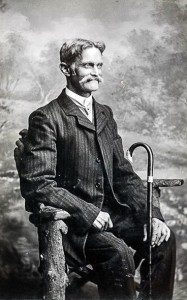

Bill Minchin in his younger days, when he’d be delivering bread on his horse and cart. This uncropped version – in his Sunday best – comes courtesy of Simon Bartrum, whose grandmother Florence (1894-1987) was Bill’s youngest sister

A circular showing the bake house, grocery and confectionary shop in the High Street, about 1885. After moving to Bourton 25 years later, May would have called in to buy bread and cakes for the Moores, her employers. Also Bill would have made a regular delivery in his horse and cart – like the man in the picture. There were many opportunities to meet.

This is probably Bill’s horse and cart outside Wilkins’ Lower Mill, Bourton, photographed in 1936. He’s probably inside, just out of sight. CLICK TO ENLARGE. When they were not at school, his daughters Eileen and Peggy would go out with him on his bread round. Wives would welcome him, giving him a cup of tea or a glass of cider. He probably preferred the latter.

This is Wilkins’ heavy duty wagon for moving flour to the bakery. Bill would drive this too. Photo about 1920, at the time of his marriage to May.

Bill was probably still living here in a cottage in Sherborne Terrace with his parents, John and Ann, when he met May. Now fashionable, it would then have been overcrowded and impoverished.

Bill’s father John. He lived until 1922 and so would have been present to attend May and Bill’s wedding in 1920 and to see their first baby, Eileen, born in 1921. He worked as a domestic gardener. SEE ARTICLE JOHN AND ANN MINCHIN ON THIS WEBSITE.

Bill’s mother Ann, who died in 1916. She worked as a laundress, taking in laundry. Hence her own clothes are neatly pressed here. This could have been around her wedding in 1876. SEE ARTICLE JOHN AND ANN MINCHIN ON THIS WEBSITE.

In 1919, one year after the war ended, May caught pneumonia and was admitted to hospital in Cheltenham. She was seriously ill, there being no antibiotics to combat it, and her life hung in the balance. While in a fever, she lost all her hair. Every night, even after his long day’s work, Bill cycled the 14 miles to Cheltenham to sit at her bedside, then cycled back, snatching just a few hours sleep before rising at dawn to get to the bakery.

The next year, 1920, Bill and May married at St Lawrence’s. By then, both May’s parents were dead, as was Bill’s mother. But his father John was still alive and would have certainly been able to attend the service, along with Bill’s brothers and sisters. John was still alive when May gave birth to their first child, Eileen – his grandchild – in 1921. He died in 1922.

May’s Auntie Ada was also still alive and keeping in touch although she had returned to the Liverpool area. She may have attended.

Bill and May moved to a house at the rear of the Victoria Hall. It was handy for Bill who liked to pop across the road to play billiards there during his limited free time. He was one of Bourton’s best players. As for the rest of the family, as the years passed, they would go to watch the latest movies upstairs at the Hall. It was Bourton’s only cinema and opened their eyes to a bigger world, of London and Hollywood, beyond insular village life.

The house where May and Bill moved to. Their eldest daughter Eileen would peer from her bedroom window and see the rear of the Victoria Hall where her father played billiards. Later they moved to 12 Rissington Road.

Apart from billiards, Bill also took part in football in the river every August Bank Holiday. It was fun and Bourton was savvy enough to realise it drew in the tourists. This picture was painted in 2002 and shows the Minchin’s first home (much edited!) behind. It hangs in Victoria Hall.

The years slip by . . .

In 1944, their eldest daughter Eileen Dale, who was married but still living with her parents at Bourton – by then at 12 Rissington Road – travelled by train to Liverpool to visit her Great Auntie Ada (shown in the top picture) who by then was 71. It was wartime and Eileen’s husband Ken was with the Eighth Army in Italy. She took her two-year-old daughter Susan who sat on Ada’s lap just like May had done more than 50 years before. Eileen remembers Ada as being a ‘very grand old lady’.

On the evening of 21 August, 1987, Sally Northfield and her mother Peggy Riding were with May at Peggy’s home in Blisworth. Sally said: ‘We managed to get my grandmother to recite Dolly Sat At The Window and write it down – so glad we did. Well, here it is…’

May was 95 by then but she could still remember it perfectly. Rather surprisingly, nothing comes up about it on Google, so Sally’s record is doubly valuable.

Dolly sat at the window

Dolly sat at the window

Staring out at the rain

As it came in little channels

All down the window pane.

Dolly was cross

She had been grumbling

At everything all day long.

‘It’s all as horrid as could be,’

Was her dreary little song.

Kind nurse had tried hard to please her

And made her hot toast for tea.

But Dolly was out of temper

And as cross as she could be.

‘I’ll have no tea at all tonight

‘But I’ll watch the passers-by.’

So Dolly turns her head aside

And heaves a heavy sigh.

Just then a little ragged girl

Came along the dirty street.

Her little bare feet showed

She stopped before Dolly’s window

And looked into Dolly’s face

With its bright room full of comfort

And the tea laid in its place.

There her longing eyes rested

And then she stretched out her hands

With a hungry cry to Dolly

Who there at the window stands.

And Dolly,

Seeing the thin hand

And hearing the poor child’s plea,

Forgets her crossness and tempers

And turns round to fetch her tea.

With hot toast, thin bread and butter,

Dolly’s fat arms are soon piled.

She carries it all to the window

And gives it to the hungry child.

The child’s face lights up with gladness,

Happy the child has become.

With thanks and joyful greetings

She hurries to her poor home.

It is always the way dear children,

If you’re cross and all goes wrong.

Find someone who is poorer and sadder

And try to help them along.

You’ll find your temper will vanish

And you’ll want to grumble no more

And you’ll think your own lot sweeter

Than it ever was before.

May at about 70, perhaps at 1963 wedding of Susan Dale to John Waite. SEE SUSAN DALE AND JOHN WAITE: THE EARLY YEARS, ON THIS WEBSITE

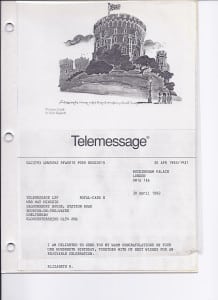

30 April 1992: A telegram from the Queen on May’s 100th birthday. It was amongst many congratulations she received at a birthday party held at The Warren, Bourton.

The top photograph was sent by Chris Clark. Perhaps others can give further details and interpretations.

Side by side at the end. Bill and May returned to St Lawrence’s where seven decades earlier they had wed.

May in her later years in Bourton. Her prettiness still shone through. She died in 1994 aged 101. Hers was an exceptionally productive life which, while never qualifying for the history books, can now be recognised on websites like this.

Uncle Will – William Wood, May Minchin’s brother, probably about 1920. This photo was found by Chris Clark at the home of his mother Thelma in Cleethorpes. On the back it says: “Thelma’s uncle William Wood.” Chris recalls: ‘I can just remember him as an older man as he used to call in at Rissington Road in August, having come to Cheltenham for the cricket.’