Eileen & Ken: The War Years

Love in a Time of War

By John Dale

It was 1937 and Ken Dale had just arrived in the Cotswolds. He was 19 years old and, to him, it was a strange part of the country. He was one of thousands of men being deployed by a government in London which was growing fearful of Hitler’s Germany. Britain was in a race to rearm and he was set to work building an aerodrome at Little Rissington. The men were lodged in the surrounding villages where their money and free-spending brought relief to families still struggling to escape the Great Depression.

He found lodgings in Moore Road, Bourton-on-the-Water, and one Sunday evening he decided to attend the service at St Lawrence’s church nearby. Amongst the congregation, he noticed a girl who was wearing a Tyrolean hat, a then fashionable style which she had adopted from the movies shown every week at the Victoria Hall. She glanced round and their eyes met before she looked away. It was only a fleeting moment but Ken nudged his friend and said: ‘That’s the girl I’m going to marry.’

But how was he to meet her? A few days later, fate intervened. He was at a dance in nearby Naunton and there she was again, and again they exchanged fleeting glances.

My father had arrived in Naunton with another young woman but she was accompanied by her mother, which he considered an impediment to his romantic aspirations. So when he stepped out onto the dance floor, it was not with her. It was with the girl in the Tyrolean hat. As he led her in a waltz, she thought this outsider was a cut above the local farm boys. She liked him for his reserved manner which verged upon shyness. Yet he was obviously determined. They danced all evening.

Eileen Minchin was 16 years old and and afterwards they got on the bus and sat together for the journey back to Bourton. As they disembarked, he asked her: ‘Can I see you tomorrow evening?’ She hadn’t had a boyfriend before and replied shyly: ‘Yes.’

Next evening Ken had a quick half pint in the New Inn to buck himself up, then stood across the road as arranged. Eileen peered from the bedroom window of her home at 12 Rissington Road to check he was waiting. When she saw he was there, she went along. They set off on a walk, which took them back past her house. After a while, Ken noticed they were not alone.

‘There’s two girls behind us,’ he said. ‘When we stop, they stop. When we start walking, they start walking.’

‘Ignore them,’ replied Eileen.

‘Who are they?’ he asked. ‘And why are they following us?’

‘Oh,’ said Eileen, ‘it’s just my sisters being silly.’

At 14, Eileen left school and began work here. It was then Gilbert’s, Bourton’s main grocery shop. She’d be alarmed by the newly arriving labourers with rough accents she could not understand. But after them came the tradesmen and she met Ken, who seemed different.

After that Eileen and Ken met every evening, usually with Nancy and Thelma dawdling a few paces behind. She took Ken home to meet her mother, May, who approved so much she offered him lodgings. Ken moved in, paying £2.50 for full board and taking the small front bedroom. Eileen and her sister Peggy shared another bedroom. The main bedroom had two beds, one for May and Bill, the other for Nancy and Thelma. Bill would invite Ken to play billiards at the Victoria Hall and for the odd glass of beer or scrumpy at the Old New Inn. He soon became part of the family and May would serve him larger portions at mealtimes, prompting Bill to glare and say: ‘Who’s the lodger here?’ Bill was strict, telling his daughters: ‘If you get into “trouble”, you’ll go in the workhouse.’

Till Hitler us do part

Ken Dale was born on 19 September 1918. On that day the Great War was still raging, although the Germans were in a final retreat. It would end seven weeks later.

He was raised in the Lincolnshire Wolds and started work at 14, becoming apprenticed as a joiner (See The Lost World on this website). As an only child, he thought he was lucky to join such a happy household as the Minchins. May was so proud of him she used to carry his photo and show it to everyone in the village. She’d given birth to four girls and Ken was like the son she’d never had. It was what she felt and what he felt in return.

But that idyllic life was cut short in 1939 when the predicted war against Germany drew near and military conscription was put into effect. Men of fighting age were mobilised and Ken was called up into the Army. On 17 July he joined the territorials of the Royal Artillery. On the day Britain declared war, 3 November, he was ’embodied’ into the unit. He was reduced to a number which he had to be able to say in an instant: 1498734. He had to leave Eileen and her family and was sent to various parts of the country, returning on leave as often as he could, clumping up the garden path in his polished boots and khaki battledress and carrying his kitbag on his shoulder. As a tradesman, he had valuable skills and on 14 March 1941 he was transferred to the Royal Army Ordnance Corps where he was trained as an instrument mechanic specialising in maintaining big guns. At different times, he was based in Fort William, Scotland, and at Nottingham University – where Eileen visited him by bus, being sick on her red-spotted dress. Then he was in Woolwich, London, where he would travel through tube stations packed with families sleeping on the platforms to escape from the Blitz and bombing overhead. War was dominating his life but he had yet to see action.

In 1941, he was told he would be going overseas, probably for a long period. He wasn’t told where. It was a military secret. Since that first dance at Naunton, he and Eileen had always known they would marry and now they brought their plans forward. He needed Army permission and it was granted.

Inside St Lawrence’s, where Ken and Eileen first saw each other. Four years later they stood here and swore their wedding vows, returning up the aisle as husband and wife.

Under a blue sky on a frosty Monday, 22 December 1941, they both returned to St Lawrence’s, the church where they had exchanged that first glance. Ken was in a double-breasted pinstripe and clutching dress-uniform white gloves. He stood nervously at the altar with his best man, Ken Buckingham, under the moist eye of May sitting in the front pew. Eileen entered on the arm of her father, Bill. She was wearing a pink crepe dress and matching bolero jacket, and hat which she had bought in Cheltenham. She had two orchids pinned to her lapel. She was followed by her bridesmaid Peggy. As the bride proceeded down the aisle, all faces turned towards her.

One of those faces in the front pew belonged to Ken’s mother, Alice Dale. She had travelled south from her home in Lincolnshire, on what was probably the longest journey of her life. It was the first time she had met the Minchins. As the Rev. Robert Drury conducted the service, they sang two hymns, Praise My Soul The King Of Heaven and Love Divine. Ken and Eileen stood side by side and uttered their vows which seemed unfortunately apt in the middle of the greatest war the world had seen: Till death us do part…’

The Rev. Robert Drury took the service and led Eileen and Ken in their vows. As the organ struck up, he introduced the hymns, Praise My Soul The King of Heaven and Love Divine. These remained their favourites and years later, at Sunday teatime, they would hold hands and sing them softly during BBC TV’s Songs of Praise, a programme they hated to miss.

As he slipped the ring onto her finger, Ken gazed into Eileen’s eyes and neither knew what really lay ahead. No one did. Not Churchill. Not Hitler. With Britain struggling to survive, marriage was more an act of individual faith and hope. Would Ken go away and never return? Would the war be won or lost? Truly they were bound together in holy matrimony but what did that mean when lives were being lived in the shadow of death?

The wedding reception. Alice Dale is seated second from left. Best man Ken Buckingham, Ken, Eileen (in a pink crepe dress and matching bolero jacket), Bill Minchin. At front Thelma (standing), Peggy, their mother May and Nancy (standing, right).

The church was like a sanctuary. The hymns and prayers offered a brief respite from the headlines dominating the outside world. The Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbour. The Germans were besieging Moscow. Bombs were falling on British cities. Ships were being sunk in the Atlantic, drowning hundreds of young men. Young men like Ken. There would be a third element necessary in this marriage. Luck.

Through that marriage, Ken became the first of the males who would each in turn be adopted as an honorary member of the Minchin family. Over time he would be followed by Vic Riding, John Moy and Reg Clark as Peggy, Nancy and Thelma each took a husband. It gave the men an additional sense of belonging for which they would always be grateful. This was especially so in Ken’s case because he had been an only child who had felt isolated in his early country life.

After the service, everyone walked from the church, down the High Street and across the river to the Studio Cafe, behind the Victoria Hall. The reception was a gift from the owner, Mr Dawkes. Eileen had worked for him in his antiques shop as a young girl. Even then, Bourton was popular with tourists, mainly from the Midlands and, before moving to Rissington Road, the Minchin family had live in the house next door.

This is where the Minchin family lived before Rissington Road. Eileen’s bedroom window used to look out onto the rear of the Victoria Hall. When very young she worked at the antiques shop, now the perfumery. The wedding party trooped through the archway to the reception at the Studio Cafe, once the site of The Woodman Inn.

Ken and Eileen set off on honeymoon. They caught a train from the station in Station Road and travelled by locomotive, bus and foot to Wold Newton for their honeymoon. They spent Christmas at Scallows Hall where Alice worked as housekeeper (see also The Lost World of Wold Newton).

They celebrated Christmas there. Afterwards Ken returned to the Army and Eileen to her parents in Bourton. He was able to come back most weekends by train.

Three months later, Eileen received a telegram asking her to go to Wakefield, Yorkshire, urgently. She caught the train and was met by Ken. He said: ‘We’ve got our orders. We’re leaving tomorrow.’

She said: ‘I think I’m expecting.’

As she uttered the words, they both realised that Ken might not see the baby for a long time, if ever. He’d been promoted to sergeant and she sewed the new stripe onto his uniform. Next morning he was up at 4am. The streets were pitch black because of the blackout. She could just see him as he set off down the road in his combat uniform, kitbag on his shoulders. He kept turning and waving and she waved back until he disappeared into the darkness. She didn’t cry. Parting and sadness were embedded in wartime life. It was government sponsored, a patriotic duty, part of everyone’s contribution to the collective effort.

At 10am Eileen got to Wakefield railway station to return to Bourton and boarded a train. She found a seat and wandered into the corridor, seeing hundreds of soldiers milling about on the platform opposite. As her locomotive blew smoke and steam and started to chug away, she noticed one of the men raising his hand and beginning to wave. He was smiling and waving frantically. He was looking straight at her. She stared and next moment she was waving back, just as frantically. It was Ken. He’d known which train she would be on and had found a spot at the end of the platform. Now they waved in a desperate last exchange as the train gathered speed and pulled them ever further apart. She continued, leaning out of the window until he was just a dot, and then he was gone. She gazed at where he had once been. Perhaps this was an omen. Surely, this would not be the end? Surely she would see him again, wouldn’t she? Surely, Ken would return one day to see her and their child, as yet unborn…

Eileen returned to her seat and the train carried her towards home and Bourton.

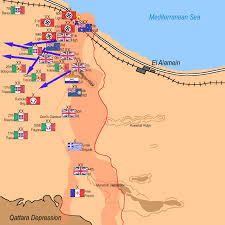

Showdown at El Alamein

Even Ken didn’t know where he was going. Troop movements were military secrets. With a photo of his wife in his breast pocket, he boarded the train at Wakefield and a few hours later he arrived at Liverpool. He was herded on board a liner which had been converted into a giant troopship. Sleeping on the decks as well as down below, the soldiers filled every inch of space as it set set sail. It was a tempting target for German submarines. It would have been a disaster – militarily as well as personally – if it had been sunk. But for this reason it was part of a protected convoy as it turned south towards the sun. A few days later it was making its way at full speed down the West Coast of Africa. As the ship crossed the Equator, only the most imaginative would have been able to tell themselves they were on a luxury cruise. The heat was unbearable for all those young passengers who had never been out of the British Isles before. The vessel must have been like a steel oven. It rounded the Cape of Good Hope – the tip of South Africa – and turned into a busy port to take on more fuel and fresh supplies. The troops disembarked briefly and Ken explored the bazaars and saw a street show given by a snake charmer. He was also able to write a letter to Eileen. Despite the censors, it said he was in the city of Durban, thereby letting slip a military secret. Fortunately there were no German spies in Bourton (as far as is known!)

Then the soldiers reboarded and sailed up the East African coast, back across the Equator and into the Red Sea. The ship delivered them to the throbbing Egyptian port of Suez.

Watch out, Rommel. Muscle Beach, North Africa 1943. I think Ken, soldier 1498734, is 4th from right standing.

Through training, Ken would have been well acquainted with the demands of military life. But it must have been an eye-opener, a contrast to what he had known. Not much earlier he had been in a frosty England, getting married in a quinintessential village church, appearing proudly with his bride on his arm. Now he had twice crossed the Equator, felt the burning heat of the Equatorial sun and was experiencing the sweat and dust of North Africa. Although Army life was not easy, he found it exciting, not least because he was part of the fresh new forces being assembled under General Bernard Montgomery, known as ‘Monty’.

Ken was playing his role in history, even if the glory was shared with 220,000 other men in the Eighth Army. It was a pivotal moment. Three years in and the British Army had only experienced defeat after defeat. The Germans seemed invincible especially under the ‘Desert Fox’, General Irwin Rommel.

Now Ken saw Monty touring the troops and heard him address them in his clipped accent, raising morale and preparing them for the ordeal ahead. Monty told them: ‘Every soldier must know before he goes into battle, how the little battle he is to fight fits into the larger picture, and how the success of his fighting will influence the battle as a whole.’

Now Ken saw Monty touring the troops and heard him address them in his clipped accent, raising morale and preparing them for the ordeal ahead. Monty told them: ‘Every soldier must know before he goes into battle, how the little battle he is to fight fits into the larger picture, and how the success of his fighting will influence the battle as a whole.’

As an instrument mechanic, Ken’s contribution was to maintain the big guns. On 1 October, a new regiment was founded, the Corps of Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, and he was transferred to it. He rode a motorbike around the military camp which was as large as a city. The heavy artillery was fundamental to Monty’s strategy.

On 23 October 1942 the Battle of El Alamein began with an unprecedented artillery barrage which broke the German defences. British tanks and infantry followed up and after 11 days of fighting, they achieved their first major victory. It turned the tide of war.

Ken was part of that triumphant force which enabled the Prime Minister Winston Churchill to declare on 10 November: ‘Now this is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.’

Churchill’s speech was relayed everywhere, in newspapers and over the radio. Eileen watched the films in the cinema upstairs in Bourton’s Victoria Hall and saw the Pathe News report about El Alamein and said to her friend Beryl: ‘I wonder if that’s where Ken is. I wonder if he’s in the Eighth Army.’ She felt a sense of pride but she had no way of knowing for sure. She received letters but they were heavily censored and her replies were simply addressed to Sgt Ken Dale by number, not location.

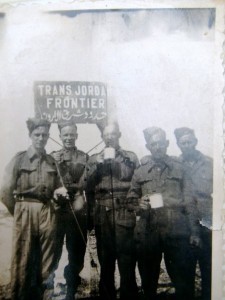

At one point, Ken was part of a convoy which drove trucks and supplies across Jordan and Syria to Basra in Iraq. I only know this because 38 years later I called him from Basra – in 1981, during the Iraq-Iran War – and he said he had been there. Also a photo (below) shows him on the Trans-Jordanian border.

Ooh, what a lovely surprise

But naturally Eileen had other things on her mind. The excitement was not confined to Ken and the North African desert. Her pregnancy had gone well yet she was impatient. At one point she spent a week in the maternity ward at Moreton-in-the-Marsh but was unhappy. All the other women were visited by husbands who were farm workers and therefore spared military service. It brought home to Eileen her own precarious situation, with Ken fighting somewhere she couldn’t even name.

She went back home and waited and then late one Saturday she felt pains and guessed she was in labour. By the time she realised the baby would not wait, it was after midnight on 21 November 1942 and Bourton was in total darkness because of the blackout. There were no facilities for delivery in the village. They needed to get to Moreton-in-the-Marsh eight miles away.

Bill raced off on his bike to Moore Road to raise Mr Buffin, who ran a taxi service, while Eileen stayed with her mother and sisters and a neighbour, Mrs Collett, who had nursing experience. The baby was determined to be born. She was in agony yet no taxi arrived. Bill came through the door, puffing and panting, and said: ‘I’ve knocked on the door but I can’t wake Mr Buffin.’

The women stared at him in dismay. He must have seen the state Eileen was in. May said sharply: ‘Well, she’s having the baby right now and so you’ll have to go back and do whatever you can to wake him.’

Bill took one look at Eileen and realised he had no choice. He raced off again and this time threw pebbles at the bedroom window until a face appeared. Mr Buffin opened the door and Bill said: ‘We have to get Eileen to Moreton.’

The car arrived outside 12 Rissington Road and Eileen was helped out of the house by her mother and Mrs Collett, watched by her three alarmed sisters. She had difficulty walking down the slope because the baby was already being born, its head emerging. She got in the backseat and they set off. They’d only got past the New Inn, where the road curves, when she cried out: ‘The baby’s here. It’s arrived.’

They stopped the car opposite the post office and did what they could. Then they resumed the journey, with Mr Buffin driving carefully. The journey seemed to take for ever and when they arrived at Moreton, the nurse peered inside and said: ‘You look all right, Eileen – but it’s a cold night and I’m worried about the baby.’ The baby was rushed inside and placed in an incubator.

Born on the back seat. The car set off with three people and arrived with four! Eileen sent Ken this photo. He put it in his battle tunic’s breast pocket and carried it through the fighting, worried Susan was growing up without ever seeing her daddy.

A few weeks later the Army postal service delivered a letter somewhere in the North African desert, into the hand of Ken who was anxiously waiting for news. He tore it open and out fell a photo of a baby girl with a mop of black hair. The accompanying note said: ‘This is out baby daughter, Susan Janice. Love Eileen.’

Watch out, Mr Hitler. Ken on left. Sign says Trans Jordan Frontier. Must be when he drove trucks to Basra. He carried the pictures of Eileen and Susan in the breast pocket of his battle tunic.

He put the picture in the breast pocket of his battle tunic next to the one of Eileen. It would remain there, through fights and beach landings, barrages and bombardments.

While the Eighth Army fought its way across North Africa, the women of Bourton did their bit for the war as well. At night Eileen and Peggy went firewatching in case German bombers came over to attack the aerodrome at Little

Rissington, the one Ken had helped build.

‘We never had to put any fires out,’ said Eileen later. ‘The American airmen would come and chat to us. We were very young and Peggy and I would just look at each other and giggle.’

‘I know we’ll meet again some sunny day’

Meanwhile, the Eighth Army continued to chase the Germans westwards and across the Mediterranean. Against great firepower, the British made a beach landing in Sicily. There were considerable losses and Ken, as a man who knew how to cut wood, was deployed in the military branch of undertaking, making coffins and burying the dead.

Later, he would avoid talking about it. He refused to watch the movie Saving Private Ryan, with its realistic beach battle, saying: ‘I’ve seen enough to never want to see it again.’

At one point a letter arrived for Eileen, from one of his Army mates.

‘Ken is in the American hospital,’ it said. ‘He was crossing a bridge on his motorbike when it was blown up.’

He was treated and soon returned to his duties. For the rest of his life, he carried a visible scar on his shinbone.

By now, with his other work, Ken was helping to handle the ever larger numbers of surrendering prisoners. As his regiment made its way up the leg of Italy, he sent Eileen a broach of coral stone, which she lost in the Plaza cinema, Grimsby.

The military postal service was amazingly efficient in the circumstances. Monty said his soldiers could march for three or four days without food on the strength of one letter from home. Susan had turned from baby to toddler and Eileen told her about the daddy she had never seen. Every morning Susan watched from the bedroom window for the postman and sometimes there would be a letter in an Army envelope from her father. Eileen would say to Susan: ‘We are going to write a letter to Daddy.’ Susan would hold a pencil and scribble on a sheet of paper while Eileen wrote actual lines on another. They’d listen to Vera Lynn singing on the radio and Eileen hoped, like millions of other forces wives and sweethearts and mums and dads, that the words would prove prophetic and true…‘We’ll meet again, don’t know where, don’t know when…but I know we’ll meet again, some sunny day…’ It was a voice and song which carried so much hope and faith and would always remain one of her favourites.

For Eileen, there was the constant worry that one day the postman might be replaced by the telegram boy parking his red-framed bike against the garden gate and walking apprehensively up the garden path. In one sense it was such a ordinary act, in another a heartstopping moment. Telegrams were met with terror, dread and shaking hands. People would be afraid to open them and, when they did, the short message often triggered wails of lament. We regret to inform you… The telegram boy would bring home the horrible realities of war – the deaths, the maimings, the missing in actions – and destroy the shallow idyll of gentle communities like Bourton.

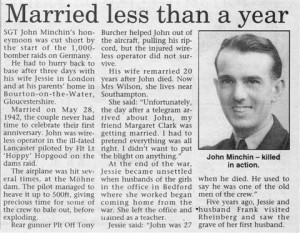

Indeed two Bourton Minchins – John and Ronald, both sons of Bertram and Eliza Minchin – died within six weeks of each other in 1943. John, 27, a wireless operator/air gunner, was taking part in the Dambusters Raid in May. Ronald, 23, a sergeant, died serving with 295 Squadron in June. Their names are next to each other on the Bourton War Memorial on the village green. They were a separate branch of the Minchin family but I give their details here:

Minchin John William Sgt, W/Op-Air Gnr 1181097, 617 Sqdn, Royal Air Force, died 17/5/1943 age 27. Son of Bertram and Eliza nee Hall, husband of Jessie Kate of Bedford and brother of Ronald who also fell. Buried in Rheinberg War Cemetary, Germany.

Minchin Ronald Buckland Sgt 1312801, 295 Sqdn, Royal Air Force died 27/6/1943. Son of Bertram and Eliza. Commemorated on the Runnymede Memorial, Surrey.

My father took me to see The Dambusters film at the Regal, Grimsby, in 1955. No one mentioned the Minchin/Bourton connection. John Minchin was on board M-Mother, the second Lancaster to attack the Mohne Dam. It was hit by shrapnel and started to burn and he was badly wounded. A comrade pulled his ripcord and pushed him out of the hatch. Moments later the plane exploded. He did not survive.

Bourton War Memorial unveiling 7 December 1920. Bill Minchin worked in the bakery opposite on the High Street and four weeks earlier, on 6 November, had married May Wood at St Lawrence’s church, Bourton. Is he standing in the crowd above, cap in hand, head bowed? Or is he on his horse and cart fulfilling the equally important task, that of delivering the daily bread around the village? Is May in the picture? Both would have known many, if not all, the 27 names engraved on the Memorial. Bill would have grown up with most as his friends. Twelve more were added after World War Two, including the Minchin brothers. Read more on this in May and Bill Minchin: the Early Days,

The Minchin brothers’ names on the War Memorial. They died in bomber raids within six weeks of each other.

Bourton also bore the memory of the Souls brothers, of nearby Great Rissington. Five of them went off to fight in the 1914-18 War. None returned. It was like a real life version of Saving Private Ryan, but worse. After that, their mother Annie would never stand for the national anthem. Why should she sing God Save The King?

http://www.bbc.co.uk/gloucestershire/content/articles/2006/11/10/remembrance_souls_feature.shtml

Mummy, where’s Daddy?

Ken’s luck held out. Whereas 60 million perished worldwide, he survived. When the war ended in 1945, he was in northern Italy, probably Milan. He received a pass and travelled by train across France towards Britain. He sent a letter ahead saying when he expected to arrive in Bourton.

Eileen recalled receiving the news: ‘We were all thrilled. He was alive, safe and coming home. He told me which train he hoped to catch.

‘Late in the afternoon I dressed Susan in her red coat and put her in her pushchair. I wheeled her to Bourton station. I stood on the platform, waiting. To Susan, her daddy was just a photograph and letters. She’d never seen him. He’d been away for more nearly four years. All through the war I’d kept telling her that she’d see her daddy one day. Now I said, ‘Daddy’s coming on the train. You’re going to see him.’ She was very excited.’

They watched as the train chugged into view and halted alongside the platform. As the cloud of steam and smoke dispersed, they saw the carriage doors being flung open. Soldiers in khaki jumped out, some into the arms of their girlfriends and wives. Eileen kept searching their faces. Where was Ken? Then the whistle blew and the train pulled out and vanished from view down the line.

‘Everyone left and Ken hadn’t arrived. I told Susan, ‘Daddy’s not come.’ She was so disapointed. I pushed her back to Rissington Road.

‘Mum and dad and my sisters were all watching from the front window. When they saw me open the garden gate, they rushed out and asked where Ken was. I told them he wasn’t on the train. They were just as disappointed. We were worried but in those days you lived with this kind of uncertainty and, of course, we didn’t have a phone. There was no way of making contact.

‘We sat down and ate the tea that Mum had prepared for him. At six o’clock I took Susan upstairs and put her to bed. I went and sat in the sitting room with the others.

‘We were chatting about what might have happened when we heard the back door click open. A voice shouted out and we all looked round and there was the sound of footsteps, heavy ones like Army boots. Someone was walking across the kitchen towards us. Next moment he was standing there, framed in the living room doorway, and grinning at us, his face deep brown from the sun.’

At this welcome vision, they all screamed: ‘Ken!’

‘I missed the train, he said. ‘I got a later one.’

Eileen described the scene: ‘We jumped up and he hugged and kissed me, and did the same to everyone else and shook Dad’s hand. Susan heard us and woke up and started shouting from upstairs and I went up and brought her down.

‘“Here’s your daddy,” I said.

‘We’d wondered how she might really react to him. After all, he was like a stranger to her. Some children in Bourton hadn’t taken to their fathers after they’d been away for so long but straightaway Susan sat on his knee and looked so happy. She had waited for this moment. Ken gazed at her, saying, “So you’re my little girl.”’

‘Next morning, I put her in her little red siren suit and embroidered peaked cap and red shoes, and she held her father’s hand as they walked across the road. They took some bread and fed the ducks. He came back and said, “She never stopped talking to me.”

‘He was back for a month – they called it B-leave, I think – and then I went with him to Bourton station and saw him off on the train. I sobbed my eyes out. I was still crying when I got back to the house. Dad was in the garden digging his vegetables and he said, “It won’t be long before he’s home again.”’

‘He was back for a month – they called it B-leave, I think – and then I went with him to Bourton station and saw him off on the train. I sobbed my eyes out. I was still crying when I got back to the house. Dad was in the garden digging his vegetables and he said, “It won’t be long before he’s home again.”’

Again, Ken endured a long train journey. He returned to northern Italy to find he was actually being demobbed immediately. As a building tradesman, he had the kind of skills needed in war-damaged Britain. Back on the train. Back across the Channel. Back through London. Back to Bourton, this time carrying his demob suit – a double-breasted brown pinstripe to set him up in ‘Civvy Street’.

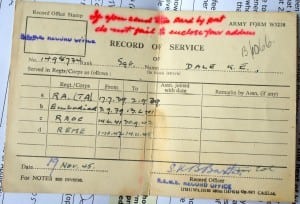

Ken’s Record of Service, from the Ministry of Defence. No. 1498734. Rank Sgt. RA. (TA) from 17.7.39 to 2.9.39: Embodied 3.9.39 to 13.4.41; RAOC 14.4.41 to 30.9.42; REME 1.10.42 to 14.11.45. Document dated 19 Nov, 45.

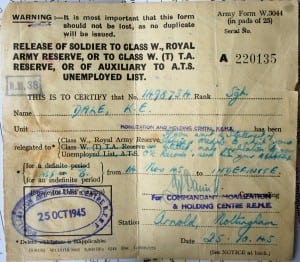

This is to certify that no. 1498734 Sgt Dale K. E., Mobilization and Holding Centre, REME, has been relegated to Class W., Royal Army Reserve, for an indefinite period from 14 Nov 45. Station Arnold, Nottingham. 25.10.45.

Bourton or Grimsby?

Hitler never did Bourton much harm directly although he did take the lives and health of a number of its sons. Compared with some parts of Britain, it was lucky. It was unscathed by bombing and the bridges and houses still turned golden every dawn and dusk if the sun was shining. By then it had another tourist attraction: the Model Village which had kept jobless farm workers busy behind the Old New Inn during the 1930s Depression. While industrial towns suffered from severe food shortages, Bourton had its own sources of vegetables and meat, with people keeping pigs and chickens, and farms supplying fresh milk and butter. Bill tended a huge garden like most of his neighbours. As well as that, he worked for a baker on the High Street opposite the War Memorial, 14-hour days which began with baking the bread and ended with delivering it on a horsedrawn cart. It meant the Minchins always had a loaf in the bin. But it wasn’t all good. Life was still hard. Opportunities were limited and pay low.

The Minchins were just one family amongst billions worldwide caught up in the greatest events of modern times. Death and destruction, famine and disease, poverty and economic ruin. The Minchins remind us that these were not faceless masses but individuals.

The Minchins were just one family amongst billions worldwide caught up in the greatest events of modern times. Death and destruction, famine and disease, poverty and economic ruin. The Minchins remind us that these were not faceless masses but individuals.

Ken was still only 26 years old and had gone through so much. Despite their brevity, the war years were probably the most formative of his life.

After the initial homecoming, the return to civilian life – ‘Civvy Street’ –triggered mixed feelings. Crime soared, marriages crashed, there was social disruption. Yes, peace brought relief from imminent death or the loss of friends and loved ones. But there was a disappointment at how Britain rewarded men who had risked their lives and endured horror first hand. The New Jerusalem for which they’d fought was slow in being built.

As a small boy, maybe five or so, I remember my mother saying we were going to visit some people and not to stare at the man because he had been ‘in Burma’, whatever that meant. When I saw him, I did stare long enough for the image to imprint itself permanently on my brain. It was impossible for a child not to stare. A living skeleton whose fragile limbs could hardly bear the weight of his suit, shirt and tie. As the tea was served, his shaking hands rattled the cup and saucer and he struggled to drink without spilling. He sat there lost in a trembling silence, locked in another world, perhaps waiting for the next beating in the Japanese prison camp that had taken over his mind.

Then there were the men from Binbrook who we would see walking down Victoria Street, Grimsby, wearing their RAF uniforms. They’d say hello to everyone, trying to quell the ill-concealed embarrassment their appearances caused. They had faces melted by fire. No lips or eyebrows. Perhaps plastic noses. They had given so much and now these were the thanks they got, the looks of frightened, ungrateful kids who had to be told not to cry or run away.

Peace brought even harsher economic conditions than war.

Although he had headed to Bourton, the terms of Ken’s demob, and the jobs available, meant returning to Grimsby. He had building skills much needed for helping to restore a bomb-damaged town. During Ken’s overseas service, his regular pay had been sent to Eileen in the form of £100 cheques. Instead of frittering it away like other wives in the stores of Gloucester, she saved it in a post office account. She didn’t want to live in a council house. She wanted to use it as a deposit for buying their own place.

Eileen and Susan said goodbye to 12 Rissington Road and travelled north, to another world. When she first saw Grimsby, Eileen was shocked and wondered if she had been wise. It could not have looked more different from the Cotswolds towns she was used to. She’d never seen a bomb site before and now she saw plenty, and anyway there were slums and poverty and dereliction which were legacies of the Depression, nothing to do with Hitler. But she got over it quickly and realised what was really important. To her, all that mattered was that Ken had survived the war and they were together and she no longer lived in dread of the telegram boy’s knock. She stayed with Ken’s mother Alice in Groom’s Cottage, Wold Newton – Alice had married Harry Lambert in 1943 – while seven miles away, Ken lodged with Mrs Wilson in Patrick Street, Grimsby. He worked in a team of men repairing and clearing away old and collapsing buildings around Grimsby Market Place.

Away from him, Eileen felt isolated. Wold Newton with its single road seemed not just another world but a lost world, one marooned in an Edwardian past, and run by a man Alice called ‘Master’, Squire Wright. (See ‘Lost World’ on this website.) It had nothing like the social life of Bourton. So she moved in with Ken in Patrick Street while he looked for somewhere more suitable. He found a terraced house at 3 Harrington Street, Cleethorpes, which had been occupied by soldiers and needed some repair. He had the energy and ability. It was just what they were looking for and they bought it on a mortgage for £450 and got their foot on the ‘property ladder’ (although it was not then seen in those terms). They slept on a mattress on the floor, with Susan in her cot sent from Bourton. Furniture was on dockets and they bought a bed from the Imperial store, cash only. Alice bought them a three piece suite. Ken soon knocked the place into shape. He did that while working 11 hour days, sometimes seven days a week – a 77-hour week of clambering on rooftops, often in freezing weather. He saw that Cleethorpes Council wanted a wheelwright. As a boy, he had learnt in the blacksmith’s how to make wooden wheels, hammering red hot metal around the rims and then plunging them into cold water. But he guessed, rightly as it transpired, that wooden wheels were not the future.

Away from him, Eileen felt isolated. Wold Newton with its single road seemed not just another world but a lost world, one marooned in an Edwardian past, and run by a man Alice called ‘Master’, Squire Wright. (See ‘Lost World’ on this website.) It had nothing like the social life of Bourton. So she moved in with Ken in Patrick Street while he looked for somewhere more suitable. He found a terraced house at 3 Harrington Street, Cleethorpes, which had been occupied by soldiers and needed some repair. He had the energy and ability. It was just what they were looking for and they bought it on a mortgage for £450 and got their foot on the ‘property ladder’ (although it was not then seen in those terms). They slept on a mattress on the floor, with Susan in her cot sent from Bourton. Furniture was on dockets and they bought a bed from the Imperial store, cash only. Alice bought them a three piece suite. Ken soon knocked the place into shape. He did that while working 11 hour days, sometimes seven days a week – a 77-hour week of clambering on rooftops, often in freezing weather. He saw that Cleethorpes Council wanted a wheelwright. As a boy, he had learnt in the blacksmith’s how to make wooden wheels, hammering red hot metal around the rims and then plunging them into cold water. But he guessed, rightly as it transpired, that wooden wheels were not the future.

Eileen gets another surprise

There was rationing of most foods and Grimsby, scarred by poverty was living upto its grimness. Many years later my father told me he had found the sheer physical demands of earning a living in the late Forties to be hard and depressing, especially after the adventures offered by the war. He only said it to me once. He was resilient by nature and did not like to dwell on weakness.

Eileen conceived a second time in August 1945, only weeks after Ken’s demob. By the time her pregnancy was well underway, she was getting used to Grimsby. Although it was by then the world’s most prosperous fishing port, and probably the biggest, its people were rough and ready in a way she had never experienced in the more genteel Bourton. There was drunkeness on the streets and cut-price vice in the alleyways. In the morning she’d hear the clip-clop of wooden clogs passing her front bay window as workers clumped their way to the fish docks. In the evenings, the Clee Park Tavern nearby, standing opposite a bomb site, would be teeming as the same people sought escape and comfort in beer and singsongs around the piano, and a bit of late-night fighting. What it lacked in gentility, it made up in character and high spirits. It was like walking on the wild side.

Back alley at 3 Harrington Street: more neglected. Funny, I recognise the bricks like old friends. Same height as a five-year-old’s trailing fingers, I suppose

There was plenty of haddock, much of it stolen and free.

Pregnant, she’d wheel Susan in her red coat and pushchair to Riby Square and Freeman Street market. When they saw her condition, other women would let her go to the front of the food queue.

She was at home when she felt familiar pains. It was Wednesday 1 May 1946, her mum’s birthday. Like Bill Minchin before him, Ken’s role was to jump on his bike, this time pedalling off to fetch a doctor or midwife. While he was away, Eileen sent Susan into the garden to play and laid down on the kitchen floor. Oh dear, it was happening all so quickly, just as it had in the back of Mr Buffin’s taxi. Why her babies wait? The labour was brief. She gave birth, this time entirely on her own. When Ken parked his bike and stepped through the back door, he found Eileen was already lying in bed nursing a son, John. Susan came in to have a look at her new little brother. Ken had never seen a newborn baby before and said: ‘Look at his tiny fingers and toes.’

To be continued…

One born on the kitchen floor, the other on the back seat of a taxi. What an impatient pair! Here they are in the back porch at their grandparents’ house in Bourton.

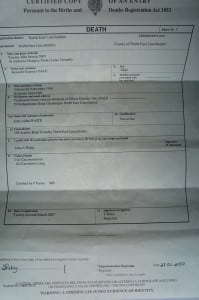

Deaths of Ken and Eileen

Working in the building trade carried serious risk in days before Health and Safety legislation. The men wore cloth caps, not helmets, overalls not high-viz jackets, and the employers and workers accepted casualties as part of the natural order, the price paid for getting buildings up (and pulled down). But, in addition to the broken limbs and cracked skulls, there was a secret (and concealed) killer: asbestos dust. Asbestos’s dangers were first shown in the early 1920s in its production in a factory in Rochdale. Workers became ill. But the evidence was suppressed and it continued to be used widely in construction and its link to lung disease took decades to emerge. It was a scandal. My father was a victim.

At the end of 2006, Ken complained of pain in his chest and it became more serious as he entered the New Year. He underwent medical checks. The consultant asked him: ‘Did you work in the building trade, Mr Dale?’ My father replied: ‘Yes, all my life.’ He had carcinomatosis and carcinoma lung. During most of his working life, asbestos was widely used in building for insulation and fire-proofing. It used to be cut and sized by men who would inhale the microfibres which would incubate for many decades. Ken would have inhaled asbestos from the 1930s onwards. It was not until the 1980s that the danger was officially recognised. He and John even built a garage out of it in Philip Avenue. Although he had once been a moderate smoker – he liked Woodbines and the odd cheroot – it was this hidden industrial disease which finally did for him. There was no compensation, of course, not that he would have expected it.

After Ken’s death, Eileen lived on her own at their bungalow at 21 Bishopthorpe Avenue, Cleethorpes. Although she missed him, she used it as an opportunity to become more independent and widen her circle of friends amongst her immediate neighbours. She was well supported by Susan and Sheila Traill, who came as a cleaner and developed into a friend, and her niece Sally and husband Alex. She also had a daily carer attend every morning and their was help from neighbours such as John and Lynn, Eileen, Pat and Brian, and her hairdresser Mark.

She proved very capable at looking after herself and was fairly contented. Her mind remained clear and active and she liked to read, especially the Grimsby Telegraph, the Mail on Sunday, Take a Break and various novels about romance in the time of WW2. She had cataracts removed from her eyes and generally her health was good. But in 2016 she started to show frailty. This worsened in 2017 but she strongly resisted giving up her independence and going into a nursing home. However this became unavoidable at the end of August. As she weakened she entered Ashleigh Court Care Home in Waltham. She died on 25 September 2017, with Susan at her bedside.

The causes of death were given as 1) Old Age, and 2) Ischemic heart disease, rheumatoid arthritis and chronic kidney disease.

The funeral was held at All Saints Church, Waltham, and was extremely well attended. It included people Eileen had worked with such as a gentleman from Hewitts Jewellers, in Victoria Street, Grimsby, and neighbours, friends and relatives. Susan did a reading and John an eulogy, part of which follows . . .

“On Ken’s return from the war, there were few jobs in teh Cotswolds and so they moved to Grimsby . Eileen adjusted to a different way of life. While Ken worked as a joiner, Eileen became a shop assistant.

“She worked in the china department at Houghtons in St Peter’s Avenue. Cleethorpes, in Hewitts the jewellers in Victoria Street, then across the road in corsets and china at Guy and Smiths, later Binns and House of Fraser. Then across the road again to the fashion emporium, Mary Coo’s.

“On Sunday afternoons Eileen and Ken would did on the sofa in the front room at Clifton Road, holding hands and listening to their records. Their favourite was Nat King Cole singing When I fall In Love, It Will Be Forever. Then, still holding hands, they’d watch Songs of Praise and quietly join in with their favourite hymns.

“Mum’s favourite TV show was Are You Being Served. She recognised life in a big department store. She fall off her chair literally at Mrs Slocombe’s double entendres, not repeatable here in church.

“Mum was a striking looking woman and enjoyed showing off her wardrobe. She and my father were regulars at the Winter Gardens displaying their waltzes and fox trots and quick step. When her sister Peggy became ill, she helped nurse her through her final days. And she would speak frequently by phone to her sisters Thelma and Nancy.

“The years slipped by and in 2001 Mum and Dad celebrated their Diamond Wedding at the Kingsway Hotel and received a lovely card signed by the Queen. She put it on display next to her pictures and flowers, family photos and her Princess Diana plate.

“How to sum up my mother? She loved Emmerdale. She adored Strictly Come Dancing. For a special Sunday lunch she liked a window table in the Kingsway looking across the Humber to Spurn lighthouse. She read the Grimsby Telegraph every day and paperback featuring wartime romances between nurses and officers who resembled David Niven. Right to the end she demanded her preferred shade of Estee Lauder foundation.

“During most of this time I was editing women’s magazines. My secret as a man was I channelled my mother: 1950s values seen through the eyes of a Grimsby housewife. Surprisingly it worked. As if by remote control, Eileen Dale imposed her valused on a magazine read by millions of women like her. Unknowingly, uncredited, she was North Lincolnshire’s cultural powerhouse.

“With support, my mother continued to live a contented life. She had a carer and she’d get up at six every morning to be ready with a cup of tea.

“But in the end even she could not hold back time. Four weeks ago she became serious ill. We knew it was serious not least when – and I am not being flippant – she expressed no interest in the new series of Strictly or the latest issue of Take a Break. She went into Ashlea Court and there they tended her with gentleness and dedication.

“The older a person is, the more they are part of your life and the more they will be missed.

“Now Eileen has gone off to rejoin Ken in the Winter Gardens in the sky. In the words of Englebert, another favourite, it’s the last waltz, and the last waltz will last forever.”